- Some suggest that a knowledge claim cannot be scientific if it does not involve direct sensory observations.

- Enhanced Sensory Observations: Using microscopes, telescopes, and other instruments to extend human senses.

- Quantitative Measurements: Gathering numerical data through instruments, such as temperature, pH levels, or radiation intensity.

- Hypothesis Testing: Formulating hypotheses based on initial observations and testing them through experiments.

- Inference from Indirect Evidence: Drawing conclusions from indirect observations or proxy data.

- Emergent Properties: Studying properties that arise from the interactions of simpler elements, such as consciousness from neural activity.

- By exploring the entire spectrum from direct sensory observations to complex inferences, the scientific method demonstrates its robustness in understanding and explaining the natural world.

Table of Contents: (Click any link below to navigate to that section.)

- Some suggest that a knowledge claim cannot be scientific if it does not involve direct sensory observations. Provide salient points along the full spectrum of scientific observation ranging from direct senses to layered abstractions and inferences.

- Outline the processes of inductive and deductive inference that allow us to confidently make claims about questions we cannot directly access with our human senses.

- Write a focused essay on what an “observation” is in science.

- Create a 10-item quiz on the entire thread above.

- Provide 20 discussion questions relevant to the content above.

Some suggest that a knowledge claim cannot be scientific if it does not involve direct sensory observations. Provide salient points along the full spectrum of scientific observation ranging from direct senses to layered abstractions and inferences.

Spectrum of Scientific Observation

Direct Sensory Observations

- Empirical Evidence: Observations made through the five senses (sight, hearing, touch, taste, smell). Examples include seeing a chemical reaction or hearing a sound.

- Field Observations: Collecting data from natural settings, such as observing animal behavior in the wild.

Enhanced Sensory Observations

- Tools and Instruments: Using microscopes, telescopes, and other instruments to extend human senses. For example, observing bacteria through a microscope or distant stars through a telescope.

- Sensors and Detectors: Utilizing devices like thermometers, Geiger counters, or pressure sensors to measure phenomena not directly perceivable by human senses.

Data Collection and Recording

- Quantitative Measurements: Gathering numerical data through instruments. This includes measurements like temperature, pH levels, or radiation intensity.

- Qualitative Observations: Descriptive data that characterizes properties without numerical measurements, such as noting the color or texture of a sample.

Data Analysis and Interpretation

- Statistical Analysis: Applying statistical methods to analyze data, identify patterns, and draw conclusions. For example, using regression analysis to understand relationships between variables.

- Modeling and Simulation: Creating mathematical models or computer simulations to predict and understand complex systems, such as climate models or population dynamics.

Hypotheses and Theories

- Hypothesis Testing: Formulating hypotheses based on initial observations and testing them through experiments. This involves designing experiments to either confirm or refute the hypothesis.

- Theoretical Frameworks: Developing comprehensive theories that explain a wide range of observations and experimental results. Examples include the theory of relativity or quantum mechanics.

Layered Abstractions and Inferences

- Inference from Indirect Evidence: Drawing conclusions from indirect observations or proxy data. For instance, inferring the presence of an exoplanet by observing the dimming of a star.

- Interdisciplinary Approaches: Integrating knowledge from various scientific disciplines to form a cohesive understanding. This might involve combining biology, chemistry, and physics to study environmental changes.

Advanced Scientific Concepts

- Emergent Properties: Studying properties that arise from the interactions of simpler elements, which cannot be directly observed but are inferred from the behavior of the system. Examples include consciousness emerging from neural activity or market trends in economics.

- Philosophical and Conceptual Foundations: Addressing the underlying philosophical questions about the nature of scientific knowledge and the methods used to obtain it. This includes discussions on the limits of observation and the role of creativity in science.

By exploring the entire spectrum from direct sensory observations to complex inferences, the scientific method demonstrates its robustness in understanding and explaining the natural world.

You’re right, there’s a misconception that science relies solely on direct observation. Scientific inquiry uses a full spectrum of evidence gathering, from the very basic use of our senses to complex abstractions and inferences. Here’s a breakdown of that spectrum:

1. Direct Sensory Observation: This is the foundation. Scientists use their senses (sight, smell, touch, hearing, taste) to gather information about the world. They note the color of a chemical reaction, the texture of a mineral, or the sound of a bird call.

2. Instrumental Observation: Our senses have limitations. So, scientists extend their reach with instruments. Telescopes allow us to see galaxies billions of light-years away. Microscopes reveal the intricate world of cells and viruses. Thermometers measure temperature precisely, and complex machines like particle accelerators probe the fundamental building blocks of matter.

3. Qualitative Descriptions: Not all observations are numerical. Scientists describe phenomena using detailed language. They might note the “milky white” color of a solution or the “erratic flight pattern” of an insect. These qualitative observations are crucial for understanding the nuances of a system.

4. Quantitative Measurements: Science thrives on precise measurement. Scientists quantify their observations by assigning numbers. They measure the mass of a star, the distance traveled by a car, or the voltage across a circuit. This allows for objective comparisons and analysis.

5. Layered Abstractions: As we delve deeper, observations become more abstract. Scientists use existing knowledge to build models and frameworks. For instance, the concept of “gravity” is an abstraction based on observations of falling objects and planetary motion. It doesn’t have a direct sensory equivalent, but it helps us understand and predict celestial interactions.

6. Inferences and Explanations: Observations are just the beginning. Scientists use them to draw inferences and build explanations. They might observe the rusting of iron and infer a chemical reaction between iron and oxygen. These inferences are based on existing knowledge and guide further investigation.

In conclusion, scientific knowledge is built on a rich tapestry of observations. From the raw data collected by our senses to the sophisticated inferences based on instruments and abstractions, every layer plays a role. While direct observation is crucial, science thrives on its ability to extend our senses, analyze data, and build a comprehensive understanding of the universe.

Science relies on various levels of observation and inference, ranging from direct sensory experiences to highly abstract theoretical models. Here are some salient points along this spectrum:

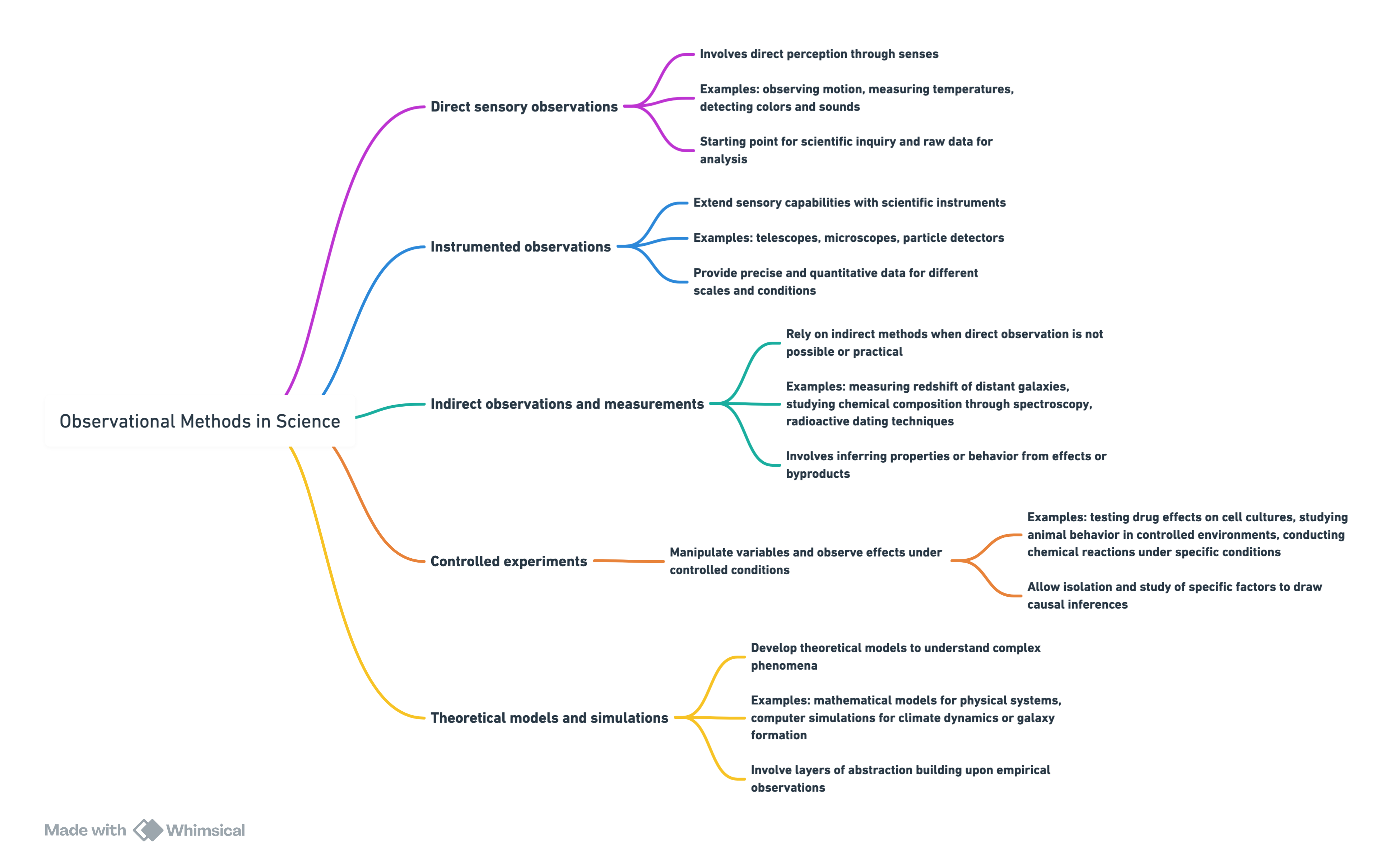

- Direct sensory observations:

- These involve the direct perception of phenomena through our senses, such as sight, hearing, touch, taste, and smell.

- Examples include observing the motion of objects, measuring temperatures, or detecting colors and sounds.

- Direct sensory observations are often the starting point for scientific inquiry and provide raw data for further analysis.

- Instrumented observations:

- Scientific instruments extend our sensory capabilities, allowing us to observe phenomena beyond the limits of our natural senses.

- Examples include using telescopes to observe celestial bodies, microscopes to study microscopic organisms, and particle detectors to detect subatomic particles.

- Instrumented observations provide more precise and quantitative data, enabling us to investigate phenomena at different scales and under different conditions.

- Indirect observations and measurements:

- In some cases, direct observation of a phenomenon is not possible or practical, so scientists rely on indirect methods.

- Examples include measuring the redshift of distant galaxies to infer their motion, studying the chemical composition of stars through spectroscopy, or using radioactive dating techniques to determine the age of geological formations.

- Indirect observations often involve inferring the properties or behavior of a system from its effects or byproducts.

- Controlled experiments:

- Experiments involve manipulating variables and observing the effects under controlled conditions.

- Examples include testing the effects of different drugs on cell cultures, studying the behavior of animals in controlled environments, or conducting chemical reactions under specific temperature and pressure conditions.

- Controlled experiments allow scientists to isolate and study specific factors and relationships, enabling them to draw causal inferences.

- Theoretical models and simulations:

- Scientists develop theoretical models and simulations to represent and understand complex phenomena.

- Examples include using mathematical models to describe the behavior of physical systems, running computer simulations to study the dynamics of climate or the formation of galaxies, or developing theoretical frameworks to explain the fundamental nature of matter and energy.

- These models and simulations often involve multiple layers of abstraction and inference, building upon empirical observations and established theories.

While direct sensory observations are crucial in science, the advancement of scientific knowledge often relies on a combination of direct observations, indirect measurements, controlled experiments, and theoretical models. Each level of observation and inference contributes to the overall understanding of natural phenomena and the development of scientific theories.

It is important to note that even highly abstract theoretical models and simulations are ultimately grounded in empirical observations and must be tested against real-world data. The interplay between observation, experimentation, and theory is a hallmark of the scientific method, and the various levels of observation and inference contribute to the robustness and explanatory power of scientific knowledge.

Click on chart to view larger version

Outline the processes of inductive and deductive inference that allow us to confidently make claims about questions we cannot directly access with our human senses.

Inductive and Logical Inference in Science

Inductive Inference

1. Observation and Data Collection

- Empirical Observations: Collecting data through direct and enhanced sensory observations.

- Repetition: Ensuring that observations are consistent across multiple instances and conditions.

2. Pattern Recognition

- Identifying Regularities: Observing patterns and regularities in the collected data.

- Correlations: Noting correlations between different variables or phenomena.

3. Formulating Hypotheses

- Hypothesis Development: Creating general hypotheses based on observed patterns.

- Predictions: Making specific predictions that can be tested through further observation or experimentation.

4. Generalization

- Inductive Generalization: Extending specific observations to broader generalizations. For instance, observing that all observed swans are white and generalizing that all swans are white.

- Probabilistic Reasoning: Recognizing that inductive conclusions are probabilistic and subject to revision with new evidence.

5. Testing and Refinement

- Experimentation: Designing experiments to test the predictions made by the hypotheses.

- Refinement: Modifying hypotheses and generalizations based on experimental outcomes and new data.

Logical Inference

1. Deductive Reasoning

- Premises: Starting with established premises or axioms that are assumed to be true.

- Logical Deduction: Applying rules of logic to derive conclusions that logically follow from the premises. For example, if all humans are mortal (premise 1) and Socrates is a human (premise 2), then Socrates is mortal (conclusion).

2. Syllogistic Reasoning

- Syllogisms: Using syllogisms (a form of logical argument) to derive conclusions. This involves a major premise, a minor premise, and a conclusion.

- Validity and Soundness: Ensuring that the arguments are valid (logically consistent) and sound (based on true premises).

3. Abductive Reasoning

- Inference to the Best Explanation: Choosing the hypothesis that best explains the observed data among several competing hypotheses.

- Plausibility and Simplicity: Considering the plausibility and simplicity (Occam’s Razor) of the explanations.

4. Mathematical and Statistical Inference

- Mathematical Models: Using mathematical models to represent and analyze complex systems.

- Statistical Inference: Applying statistical techniques to infer properties of populations based on sample data, such as confidence intervals and hypothesis tests.

5. Cross-Validation

- Interdisciplinary Evidence: Integrating evidence from multiple disciplines to strengthen inferences.

- Consistency Check: Ensuring that new inferences are consistent with established theories and empirical evidence.

Application to Indirect Questions

1. Indirect Evidence

- Proxy Data: Using indirect evidence or proxy data to make inferences about phenomena not directly observable. For example, using ice core samples to infer past climate conditions.

- Triangulation: Combining multiple lines of indirect evidence to strengthen the inference.

2. Theoretical Support

- Supporting Theories: Relying on well-established theories to support inferences about unobservable phenomena. For instance, using the theory of plate tectonics to infer the movement of continents over geological time scales.

- Consistency with Existing Knowledge: Ensuring that new inferences are compatible with existing scientific knowledge and theories.

3. Predictive Power

- Making Predictions: Using inferences to make predictions about future observations or phenomena.

- Verification and Falsification: Testing predictions through new observations and experiments to verify or falsify the inferences.

By following these processes, scientists can confidently make claims about phenomena that are not directly accessible through human senses, leveraging a robust combination of inductive and logical reasoning.

Here’s how inductive and logical inference work together to make scientific claims about things beyond our direct senses:

1. Observation and Data Collection:

- The process starts with gathering evidence through various means:

- Direct Observations: Scientists use their senses or instruments to observe phenomena.

- Existing Knowledge: Scientific understanding built upon past observations and established theories forms the groundwork.

2. Pattern Recognition and Inductive Inference:

- Scientists look for patterns in the collected data. This is where inductive reasoning comes in.

- By observing multiple instances of a phenomenon, they identify a potential rule or principle governing it.

- For example, observing apples, oranges, and watermelons all falling to the ground induces a generalization about gravity.

3. Hypothesis Formation:

- Based on the observed patterns, scientists formulate a hypothesis. This is a tentative explanation that needs further testing.

- The hypothesis should be falsifiable, meaning there should be a way to design an experiment that could disprove it if it’s wrong.

4. Deductive Reasoning and Predictions:

- Here’s where logical reasoning takes center stage.

- Scientists use the hypothesis and established scientific principles to deduce predictions about what should be observed under specific conditions.

- For example, the hypothesis of gravity predicts that if we drop a feather and a bowling ball from the same height, they will both fall at the same rate (ignoring air resistance).

5. Experimentation and Testing:

- Experiments are designed to test the predictions derived from the hypothesis.

- If the predictions consistently align with the experimental results, it strengthens the confidence in the hypothesis.

6. Refinement and Iteration:

- No single experiment is definitive. Scientists may need to refine the hypothesis, conduct further experiments, or consider alternative explanations based on new data.

- This iterative process helps build a robust understanding that transcends our immediate sensory limitations.

The Importance of Confidence Levels:

- It’s important to note that scientific claims based on inference are probabilistic, not absolute truths.

- The more evidence that supports a hypothesis, the higher the confidence level we can assign to it.

Through this interplay of inductive and deductive reasoning, scientists can make strong claims about things we cannot directly observe, building a progressively more comprehensive picture of the universe.

The process of inductive and logical inference allows us to make confident claims about questions that are beyond the direct reach of our human senses. This process involves the following steps:

- Observations and data collection:

- Researchers gather empirical data through direct observations, measurements, and experiments.

- This data serves as the foundational evidence for further inferences and claims.

- Pattern recognition and inductive reasoning:

- Inductive reasoning involves analyzing the collected data to identify patterns, regularities, and relationships.

- Scientists look for repeated occurrences, correlations, and trends in the data.

- Through inductive reasoning, they formulate tentative hypotheses or generalizations based on the observed patterns.

- Hypothesis formulation and testing:

- The identified patterns and relationships are formulated as testable hypotheses.

- These hypotheses propose explanations or predictions about phenomena that cannot be directly observed.

- Researchers design experiments or make additional observations to test the validity of the hypotheses.

- Deductive reasoning and logical inference:

- Deductive reasoning involves applying logical principles and established theories to draw conclusions from the hypotheses.

- Using deductive logic, researchers derive logical consequences and make predictions based on the hypotheses and existing scientific knowledge.

- Logical inference allows them to extend their understanding beyond the directly observable realm.

- Experimentation and verification:

- The deduced predictions and logical consequences are then tested through further experimentation and observation.

- If the predictions align with the empirical evidence, it strengthens the confidence in the hypotheses and the underlying theories.

- If the predictions are not supported, the hypotheses or theories may need to be revised or rejected.

- Theory development and model building:

- Validated hypotheses and supported logical inferences contribute to the development of broader scientific theories and models.

- These theories and models provide explanatory frameworks for phenomena that cannot be directly observed.

- They allow researchers to make further predictions, explore implications, and guide future investigations.

- Peer review and scientific consensus:

- The process of inductive and logical inference is subject to peer review and scrutiny by the scientific community.

- Through critical evaluation, replication studies, and the accumulation of supporting evidence, a scientific consensus emerges regarding the validity of claims and theories.

- This consensus lending confidence to the inferences made about phenomena beyond direct observation.

It is important to note that the process of inductive and logical inference in science is iterative and self-correcting. Theories and models are constantly refined, revised, or replaced as new evidence emerges or alternative explanations are proposed. This ongoing process of inference, testing, and refinement allows science to continuously expand our understanding of the natural world, even for phenomena that lie beyond the reach of our direct senses.

Click image to view a larger version.

Write a focused essay on what an “observation” is in science.

The Nature of Observation in Science

In science, the term observation holds a fundamental significance. It serves as the bedrock upon which scientific inquiry is built, encompassing a range of activities from direct sensory experiences to complex, instrument-assisted data collection. An observation in science is more than a mere glance at the natural world; it is a systematic and deliberate act that seeks to gather empirical evidence about phenomena. This essay explores the nature of observation in science, highlighting its methods, significance, and the challenges associated with it.

Definition and Methods of Observation

Observation in science refers to the process of systematically collecting data and information about the natural world through the senses or scientific instruments. There are two primary methods of observation:

- Direct Observation: This involves using the five senses to observe phenomena. For example, a biologist watching animal behavior in its natural habitat or a chemist noting the color change in a solution during a reaction. These observations are often recorded in a structured manner to ensure accuracy and repeatability.

- Instrument-Assisted Observation: To extend the capabilities of the human senses, scientists use various tools and instruments. Microscopes, telescopes, spectrometers, and particle detectors are some examples. These instruments allow scientists to observe phenomena that are too small, too distant, or otherwise beyond the reach of unaided senses. For instance, observing the microscopic structure of cells or detecting electromagnetic radiation from distant stars.

Significance of Observation in Science

Observations are crucial for several reasons:

- Foundation of Empirical Evidence: Observations provide the raw data that forms the empirical foundation of scientific knowledge. They are the first step in the scientific method, leading to the formulation of hypotheses and theories.

- Verification and Falsification: Observations are essential for verifying or falsifying scientific hypotheses and theories. Through repeated and consistent observations, scientists can confirm the validity of a hypothesis or identify exceptions that may lead to new insights or revisions.

- Guiding Scientific Inquiry: Observations often spark scientific curiosity and drive further investigation. Anomalies or unexpected results observed in experiments can lead to new lines of inquiry and the development of new theories.

Challenges of Scientific Observation

While observation is fundamental to science, it is not without its challenges:

- Observer Bias: Personal biases and expectations of the observer can influence what is noticed and recorded. Scientists must strive to minimize these biases through standardized procedures, peer review, and replication of studies.

- Measurement Limitations: The accuracy and precision of observations are limited by the quality and calibration of instruments. Technological advancements continually improve these capabilities, but limitations still exist, especially at the extremes of scale and sensitivity.

- Interpretation of Data: Observations need to be interpreted, and this interpretation can be influenced by existing theories and knowledge. Distinguishing between observation and interpretation is crucial to maintain objectivity.

- Indirect Observations: In many scientific fields, direct observation is not possible. Scientists rely on indirect evidence and inferential methods to draw conclusions. For example, in astrophysics, much of what is known about distant galaxies comes from interpreting the light they emit.

Conclusion

Observation in science is a deliberate and systematic effort to gather empirical evidence about the natural world. It forms the cornerstone of scientific inquiry, enabling the formulation, testing, and refinement of hypotheses and theories. Despite the challenges of observer bias, measurement limitations, and the need for interpretation, the rigor and systematic nature of scientific observation ensure that it remains a reliable means of understanding the universe. As technology advances and methodologies improve, the scope and accuracy of scientific observations continue to expand, leading to ever-deeper insights into the workings of nature.

Beyond the Naked Eye: Unveiling the Spectrum of Scientific Observation

Science, at its core, is a relentless pursuit of knowledge about the universe. But how do we gather this knowledge? The answer lies in observation – a seemingly simple concept that unfolds into a multifaceted process. While the image of a scientist peering through a microscope might come to mind, scientific observation encompasses a much wider spectrum, extending from the raw data collected by our senses to complex abstractions built upon them.

The foundation of scientific observation rests on the utilization of our senses. We see the vibrant colors of a chemical reaction, feel the warmth radiating from a star (through a telescope, of course!), and hear the rhythmic chirps of crickets. These direct sensory experiences provide the initial data points that fuel scientific inquiry. However, our senses have limitations. To overcome these, scientists have developed a vast arsenal of instruments. Telescopes pierce the veil of darkness, revealing distant galaxies. Microscopes unveil the intricate dance of life within cells. These instruments become extensions of our senses, allowing us to gather information beyond the reach of our unaided perception.

But observations are not merely passive recordings. Scientists actively describe and document their findings. They note the “iridescent sheen” of a butterfly’s wing or the “erratic wobble” of a planet’s orbit. These qualitative descriptions, rich in detail, capture the nuances of phenomena that might be lost in purely numerical data.

Quantification, however, is another crucial aspect of scientific observation. Assigning numbers to observations allows for precise comparisons and analysis. Scientists measure the mass of a black hole, the speed of light, or the voltage across a circuit. This quantitative data forms the bedrock for building and testing scientific models.

As we delve deeper, the nature of observation transforms. Scientific knowledge is not a mere collection of isolated observations. Scientists use them as building blocks to construct abstract frameworks and models. The concept of “evolution,” for example, is an abstraction derived from observations of changing life forms across generations. It doesn’t have a direct sensory equivalent, but it helps us understand the vast tapestry of life on Earth.

Finally, observations fuel the engine of inference. Scientists don’t simply record data; they use it to draw conclusions and build explanations. Observing the rusting of iron leads to the inference of a chemical reaction between iron and oxygen. These inferences, based on existing knowledge and observations, guide further investigation and propel the scientific process forward.

In conclusion, a scientific observation is a dynamic and multifaceted concept. It encompasses the raw data collected by our senses, the information gleaned from instruments, the meticulous descriptions of phenomena, the precise measurements that quantify the world around us, and the layered abstractions that help us make sense of it all. It is through this rich spectrum of observation that science unveils the hidden secrets of the universe, pushing the boundaries of human knowledge beyond the limitations of our immediate perception.

An “observation” is a fundamental concept in science that forms the foundation of scientific inquiry and knowledge. It refers to the process of gathering information or data about the natural world through the use of our senses or scientific instruments. Observations are the primary source of empirical evidence that scientists rely on to describe, explain, and understand natural phenomena.

At its core, an observation involves the careful and systematic perception of an object, event, or phenomenon using one or more of our senses, such as sight, hearing, touch, taste, or smell. Direct observations made with our unaided senses have been the starting point for many scientific discoveries throughout history. For example, early astronomers made observations of the night sky, leading to the recognition of patterns in the movement of celestial bodies.

However, as science has advanced, our ability to make observations has been significantly enhanced by the development of scientific instruments and technologies. These tools extend our sensory capabilities, allowing us to observe phenomena that are too small, too large, too distant, or too fleeting for our unaided senses. Microscopes, telescopes, spectrometers, particle detectors, and various other instruments have expanded our observational reach, revealing intricate details and patterns that were previously inaccessible.

Observations in science are not merely passive glimpses or casual glances; they are purposeful, systematic, and often guided by specific questions or hypotheses. Scientists carefully plan and design their observations, considering factors such as the appropriate instruments, techniques, and environmental conditions necessary to obtain reliable and accurate data.

Importantly, observations in science are characterized by objectivity and reproducibility. Scientists strive to minimize subjective biases and personal interpretations by following established protocols and methodologies. Observations must be reproducible, meaning that different researchers, using the same methods and conditions, should be able to make similar observations and obtain consistent results.

Observations serve as the raw material for scientific inquiry, providing the empirical foundation upon which theories, models, and explanations are built. Scientists analyze and interpret their observations, looking for patterns, anomalies, and relationships that can lead to new insights or hypotheses. These observations are then subjected to further testing, experimentation, and scrutiny by the scientific community.

It is worth noting that observations alone are not sufficient for scientific understanding; they must be accompanied by rigorous analysis, logical reasoning, and the development of explanatory theories. However, without accurate and reliable observations, science would lack the essential grounding in empirical evidence that distinguishes it from mere speculation or conjecture.

In summary, an observation in science is the purposeful and systematic gathering of information or data about the natural world through the use of our senses or scientific instruments. Observations provide the empirical foundation for scientific inquiry, serving as the starting point for the formulation of hypotheses, the testing of theories, and the advancement of our understanding of the universe we inhabit.

Create a 10-item quiz on the entire thread above.

Quiz on Scientific Observation and Inference

- What are the two primary methods of observation in science?

- How does the use of instruments extend the capabilities of human senses in scientific observation?

- Why are observations considered the foundation of empirical evidence in science?

- Describe one challenge associated with direct sensory observations in science.

- Explain the role of statistical analysis in the process of scientific observation.

- What is meant by “inductive generalization” in the context of inductive inference?

- How does deductive reasoning differ from inductive reasoning in scientific inference?

- Define “abductive reasoning” and explain its significance in scientific inquiry.

- What is the importance of integrating interdisciplinary evidence in making scientific inferences?

- Provide an example of how indirect evidence is used in scientific observation.

Answers

- Direct observation and instrument-assisted observation.

- Instruments like microscopes and telescopes allow scientists to observe phenomena that are too small, too distant, or otherwise beyond the reach of unaided senses.

- Observations provide the raw data that forms the empirical foundation of scientific knowledge, leading to the formulation of hypotheses and theories.

- Observer bias, where personal biases and expectations can influence what is noticed and recorded.

- Statistical analysis helps analyze data, identify patterns, and draw conclusions, thereby aiding in the interpretation and validation of observations.

- Inductive generalization involves extending specific observations to broader generalizations, acknowledging that these conclusions are probabilistic.

- Deductive reasoning starts with established premises and logically derives conclusions from them, whereas inductive reasoning involves formulating general hypotheses based on specific observations.

- Abductive reasoning involves choosing the hypothesis that best explains the observed data among several competing hypotheses, considering plausibility and simplicity.

- Integrating interdisciplinary evidence strengthens inferences by ensuring consistency with established theories and empirical evidence from multiple fields.

- An example is using ice core samples to infer past climate conditions.

Scientific Observation Quiz

- What is the foundation of scientific observation according to the passage?

- Aside from direct observation, how do scientists extend their ability to gather information?

- Scientific observations can include both _____________ and _____________ descriptions.

- How does assigning numbers to observations help scientists?

- What is an example of an abstract concept derived from scientific observations, as mentioned in the passage?

- The process of drawing conclusions based on observations is referred to as what in the passage?

- According to the passage, why are scientific claims based on inference considered probabilistic?

- Briefly summarize the two main types of reasoning involved in scientific inference, as described in the passage.

- In the context of the passage, what is the main limitation of relying solely on our senses for scientific observation?

- The essay mentions the importance of scientists documenting their observations. What might be lost if they only relied on recording purely numerical data?

Answers

- The utilization of our senses

- Instruments

- Qualitative, Quantitative

- Allows for precise comparisons and analysis

- Evolution

- Inference

- Because no single experiment is definitive

- Inductive reasoning and deductive reasoning

- Our senses have limitations

- Nuances of phenomena

Quiz:

- According to the information provided, what is the primary role of observations in science?

- Can observations be made solely with our unaided senses, or are scientific instruments also utilized?

- True or False: Observations in science should be subjective and based on personal interpretations.

- Mention one example of a scientific instrument that extends our observational capabilities beyond our natural senses.

- What is meant by the term “empirical evidence” in the context of scientific observations?

- Why is it important for observations in science to be reproducible?

- Which of the following is not a characteristic of scientific observations mentioned in the information provided: purposeful, systematic, or accidental?

- What is the role of hypotheses in relation to scientific observations?

- True or False: Observations alone are sufficient for achieving scientific understanding without further analysis or reasoning.

- According to the information provided, what distinguishes science from mere speculation or conjecture?

Answers:

- Providing the empirical foundation for scientific inquiry.

- Scientific instruments are also utilized in addition to our unaided senses.

- False

- Microscopes, telescopes, spectrometers, particle detectors (or any other valid example mentioned).

- Empirical evidence refers to information or data obtained through direct observation or experimentation.

- To ensure consistency and reliability of the observations across different researchers and conditions.

- Accidental

- Observations are often guided by specific hypotheses, and the analysis of observations can lead to the formulation of new hypotheses.

- False

- Science is grounded in accurate and reliable empirical observations and evidence, distinguishing it from mere speculation or conjecture.

Provide 20 discussion questions relevant to the content above.

Discussion Questions

- How do direct and instrument-assisted observations complement each other in scientific research?

- In what ways can observer bias affect scientific observations, and how can it be minimized?

- What are the limitations of relying solely on direct sensory observations in science?

- How do instruments like microscopes and telescopes enhance our understanding of phenomena that are not visible to the naked eye?

- Discuss the role of empirical evidence in the scientific method and its importance in hypothesis formulation.

- Why is it essential to have consistent and repeatable observations in scientific experiments?

- How does statistical analysis aid in the interpretation of scientific data?

- What are the differences between inductive, deductive, and abductive reasoning in scientific inquiry?

- How can scientists ensure that their hypotheses are testable and falsifiable?

- What challenges arise when interpreting data from complex instruments and how can these challenges be addressed?

- How do scientific models and simulations contribute to our understanding of natural phenomena?

- What is the role of interdisciplinary approaches in strengthening scientific inferences?

- Discuss the significance of indirect evidence in fields like astrophysics and climate science.

- How can the integration of multiple lines of evidence enhance the reliability of scientific conclusions?

- What are emergent properties, and how do they pose a challenge to direct observation?

- How do philosophical and conceptual foundations influence the methods and interpretations of scientific observations?

- Discuss the impact of technological advancements on the accuracy and precision of scientific observations.

- How do scientists differentiate between observation and interpretation in their research?

- What are the ethical considerations related to the observation and recording of scientific data?

- How can educational practices improve the ability of students to conduct accurate and unbiased scientific observations?

Discussion Questions on Scientific Observation:

- Would you consider personal anecdotes to be a form of scientific observation? Why or why not?

- Imagine a world where scientific instruments never existed. How would this impact our understanding of the universe?

- The passage talks about “qualitative descriptions.” Can you give some examples of how these descriptions might be important in scientific research?

- Are there any limitations to the use of scientific instruments? Discuss some potential drawbacks.

- How can the concept of “bias” influence scientific observation?

- The theory of evolution is mentioned as an abstraction. Can you think of other scientific concepts that are abstract but crucial for understanding the world?

- How does technology play a role in the ongoing development of scientific observation techniques?

- The scientific method relies heavily on observations that can be repeated. Can you think of any scientific claims that might be difficult to test due to limitations in observation?

- In some cases, scientific observations can be dangerous or unethical to conduct. How can scientists navigate this ethical dilemma?

- The passage talks about the interplay of inductive and deductive reasoning. Can you explain these two types of reasoning in your own words?

- How does scientific observation differ from simply noticing something in the everyday world?

- When might a scientist choose to prioritize qualitative descriptions over quantitative measurements?

- Imagine you are a scientist studying animal behavior. How could you use both direct observation and instrumental observation in your research?

- Scientific discoveries often challenge previously held beliefs. How does the concept of observation play a role in the acceptance of new scientific theories?

- Citizen science projects involve the public in data collection. How can these projects contribute to scientific observation?

- The passage mentions the concept of “confidence levels” in scientific claims. How do scientists determine the level of confidence they can place in an observation?

- Scientific observation is a continuous process. How can past observations influence the way scientists approach new investigations?

- With the rise of artificial intelligence, is it possible for machines to play a role in scientific observation? Discuss the potential benefits and drawbacks.

- In the field of psychology, studying human behavior often relies on indirect observation. How does this differ from observing physical phenomena?

- Scientific literacy is crucial for a well-informed society. How can the concept of scientific observation be used to promote critical thinking skills?

Here are 20 discussion questions relevant to the content on scientific observations:

- What role do direct sensory observations play in scientific inquiry, and how have they contributed to significant discoveries throughout history?

- Can you provide examples of scientific instruments that have expanded our observational capabilities beyond our natural senses, and how have they transformed our understanding of the natural world?

- Why is objectivity considered crucial in scientific observations, and what measures can researchers take to minimize subjective biases?

- How do scientists ensure the reproducibility of their observations, and why is this important for the credibility and reliability of scientific findings?

- Can you think of instances where indirect observations or inferences are necessary because direct observation of a phenomenon is not possible or practical?

- What is the difference between qualitative and quantitative observations in science, and when might one approach be more appropriate than the other?

- How do observations contribute to the formation and testing of scientific hypotheses and theories?

- Can you discuss the limitations of observational methods in science and situations where controlled experiments might be more suitable?

- How has the advancement of technology and computational power impacted our ability to make observations and analyze scientific data?

- What role does peer review and scientific consensus play in validating and accepting observations and their interpretations within the scientific community?

- Can you discuss the ethical considerations that scientists must take into account when making observations, particularly in fields like biology or anthropology?

- How do scientists determine the appropriate scale or level of detail required for their observations to address specific research questions?

- Can you provide examples of instances where unexpected or anomalous observations have led to significant scientific breakthroughs or paradigm shifts?

- How do scientists integrate and reconcile conflicting observations or contradictory evidence within their theoretical frameworks?

- What are the challenges involved in making observations in extreme environments, such as deep-sea exploration or space exploration, and how have scientists overcome these challenges?

- Can you discuss the role of citizen science and crowdsourced observations in contributing to scientific research and data collection?

- How do scientists ensure the accuracy and precision of their observational instruments, and what calibration or validation processes are involved?

- In fields like astronomy or paleontology, where direct observation is limited, how do scientists infer information about the past or distant phenomena?

- Can you discuss the importance of record-keeping and data management in scientific observations, and the potential pitfalls of poor documentation or data handling?

- How might advances in artificial intelligence and machine learning impact the way scientific observations are made and analyzed in the future?

Table of Contents: (Click any link below to navigate to that section.)

- Some suggest that a knowledge claim cannot be scientific if it does not involve direct sensory observations. Provide salient points along the full spectrum of scientific observation ranging from direct senses to layered abstractions and inferences.

- Outline the processes of inductive and deductive inference that allow us to confidently make claims about questions we cannot directly access with our human senses.

- Write a focused essay on what an “observation” is in science.

- Create a 10-item quiz on the entire thread above.

- Provide 20 discussion questions relevant to the content above.

Leave a comment