- “Developing a model to assess the ethical disposition of a society, as we’ve explored through our affordability framework, offers a promising tool for predicting, analyzing, and influencing moral behaviors.”

- “However, the accuracy and utility of such a model hinge on its design, assumptions, and applications, as well as its ability to navigate the inherent complexities of human ethics.”

- “Our model, which frames ethical dispositions as outcomes of psychological, social, and lifestyle ‘expenses’ balanced against an affordability threshold, captures key drivers such as compassion, resource availability, and cultural conditioning.”

- “The utility of our model lies in its potential to inform policy, education, and societal interventions by predicting ethical trends and identifying leverage points.”

- “These projects would share our model’s strengths—quantifying complex dynamics, revealing trade-offs, and guiding interventions—but face similar challenges: data limitations, cultural variability, and the risk of oversimplification.”

- “By refining the model with empirical data, dynamic simulations, and broader stakeholder engagement, we can enhance its precision and impact.”

- “Ultimately, such models are not just analytical tools but invitations to reflect on what societies can afford to value”

Table of Contents: (Click any link below to navigate to that section.)

- Can you produce a preliminary mathematical model of the dynamics for ethical dispositions of a society based on these [previously brainstormed] 13 factors?

- Let’s attempt to frame our model in terms of the “affordability” of ethical dispositions based on the psychological, social, and lifestyle “expenses”. Produce a coherent framework in these terms.

- Good. Now provide a more technical rendering of that model that should reflect the dynamics of ethical dispositions in society.

- I would now like you to comment on 1) potential causal recursivities in our model and 2) the malleability of compassion/empathy in contexts of extremely low resources.

- Now create the Mermaid Chart code that will accurately reflect our basic model of the dynamics of ethical dispositions.

- It appears we are missing a key variable: Alignment with dominant religious proscriptions. Add this to our model and Mermaid chart.

- Now, let’s apply our model to ethical dispositions found at various times in history. Let’s begin with the practice of killing or leaving female newborns to die. Provide 1) the model calculus, 2) the prose explanation, and 3) the Mermaid Chart.

- Let’s apply the model to a scenario in which much public media is emphasizing the sentience of octopi and there is reasonably-priced lab-produced meat indistinguishable from the taste of octopi.

- Write an essay that assesses the potential accuracy and utility of models created to assess the ethical disposition of a society given various factors. Comment on the possibility of other similar projects that could produce valuable models or analyses.

This is the first time Grok has been used on this site. This post is an exploration of the potential of AI-generated systems to model the dynamics of the ethical dispositions of societies, and specifically the capacity of the new release of Grok to meet this challenge.

Can you produce a preliminary mathematical model of the dynamics for ethical dispositions of a society based on these [previously brainstormed] 13 factors?

Let’s craft a preliminary mathematical model of ethical dynamics based on the 13 factors we’ve identified. The goal is to create a framework that predicts a society’s Ethical Disposition (ED)—a measure of its prevailing moral stance—at a given time. Since ethical dispositions are complex and qualitative, we’ll treat ED as an aggregate score influenced by emotional constants and contextual variables, with interactions between them. This will be a simplified, conceptual model to start, and we can refine it later based on your feedback.

Step 1: Define the Components

- Ethical Disposition (ED): A scalar value (say, 0 to 100) representing a society’s ethical tendencies, where low values might reflect survivalist/pragmatic ethics and high values reflect abstract/idealistic ethics. Alternatively, ED could be a vector for specific ethical domains (e.g., justice, care), but let’s keep it simple for now.

- Factors: We’ll assign each of the 13 factors a variable and a normalized range (0 to 1) to quantify their influence.

Emotional Constants (Stable Traits)

- Compassion (C): Empathy and care for others (0 = none, 1 = universal).

- Unassigned Righteous Indignation (RI): Latent outrage seeking a target (0 = apathetic, 1 = highly reactive).

- Fear of Consequences (F): Concern for punishment or retribution (0 = fearless, 1 = paralyzing).

- Desire for Belonging (B): Need to align with a group (0 = individualistic, 1 = conformist).

Contextual Variables (Dynamic Influences)

- Free Time for Reflection (FT): Leisure to ponder ethics (0 = none, 1 = abundant).

- Resource Availability (R): Access to means for ethical choices (0 = scarce, 1 = plentiful).

- Cultural Conditioning (CC): Strength of societal norms (0 = fluid, 1 = rigid).

- Exposure to Suffering/Injustice (ES): Awareness of moral triggers (0 = insulated, 1 = immersed).

- Information Flow (IF): Speed/volume of info spread (0 = slow/sparse, 1 = fast/abundant).

- Power Structures (PS): Degree of centralized control (0 = decentralized, 1 = authoritarian).

- Environmental Pressures (EP): External survival demands (0 = benign, 1 = harsh).

- Technological Capacity (TC): Tools enabling ethical options (0 = primitive, 1 = advanced).

- Narrative Framing (NF): Media/leader focus on ethical issues (0 = unfocused, 1 = tightly curated).

Step 2: Formulate the Model

Ethical Disposition (ED) emerges from the interplay of these factors. We’ll assume:

- Emotional constants (C, RI, F, B) provide the raw “fuel” for ethical stances.

- Contextual variables (FT, R, CC, etc.) amplify, suppress, or direct that fuel.

Let’s propose a weighted additive model with interaction terms to capture synergies:

Base Equation

Where:

- E: Emotional contribution (constants).

- V: Variable contribution (context).

- I: Interaction effects (cross-terms).

: Weights (e.g., 0.4, 0.4, 0.2) summing to 1, adjustable based on empirical tuning.

Emotional Contribution (E)

coefficients (e.g., 0.3, 0.3, 0.2, 0.2) reflect relative influence of each emotion, summing to 1.

- Example: High C pushes ED toward care-based ethics; high RI toward justice-based ethics.

Variable Contribution (V)

coefficients (e.g., 0.15, 0.15, 0.1, 0.15, 0.1, 0.1, 0.1, 0.1, 0.15) sum to 1, reflecting each variable’s impact.

- Example: High R and TC enable “luxury” ethics; high EP constrains them.

Interaction Effects (I)

Key synergies or suppressions (normalized 0–1):

coefficients (e.g., 0.3, 0.3, 0.2, 0.2) sum to 1.

- Examples:

: Indignation amplifies with exposure to injustice.

: Compassion grows when narratives highlight suffering.

: Free time + info flow boosts ethical debate.

- Negative

: Rigid power + culture stifles ethical evolution.

Step 3: Example Calculation

Let’s test it with a hypothetical society (values 0–1):

- Constants: C = 0.7, RI = 0.6, F = 0.4, B = 0.5

- Variables: FT = 0.8, R = 0.6, CC = 0.3, ES = 0.7, IF = 0.9, PS = 0.2, EP = 0.4, TC = 0.7, NF = 0.8

- Weights:

,

,

- E =

- V =

- I =

- ED =

(or 57.5/100)

This society, with strong compassion, moderate indignation, ample free time, and narrative focus on suffering, leans toward a moderately idealistic ethical disposition.

Step 4: Interpretation and Refinement

- Range: ED from 0 (pure survival ethics) to 1 (utopian ethics) seems plausible.

- Limits: This is linear and assumes equal scaling—real dynamics might need exponential terms or thresholds (e.g., RI only kicks in above 0.5 ES).

- Tuning: Weights (

,

,

,

) need historical data or expert input to reflect reality.

What do you think? Should we adjust the structure (e.g., multiplicative instead of additive), add more interactions, or test it on a specific historical case? I can also simplify it if this feels too complex!

Let’s attempt to frame our model in terms of the “affordability” of ethical dispositions based on the psychological, social, and lifestyle “expenses”. Produce a coherent framework in these terms.

Understanding the Affordability of Ethical Dispositions

Let’s reframe our model of ethical dynamics in terms of the “affordability” of ethical dispositions, interpreting “affordability” as the psychological, social, and lifestyle “expenses” a society or individual must bear to adopt and sustain a given ethical stance. This perspective shifts the focus from a static ethical disposition score to a dynamic cost-benefit analysis, where ethical choices are constrained or enabled by the resources—mental, communal, and material—available to “pay” for them. Below, I’ll outline a coherent framework, integrating our 13 factors into this new lens, to set the stage for a technical model.

Ethical dispositions—such as being compassionate, driven by a sense of justice, or holding idealistic values—aren’t just abstract preferences or moral ideals. They come with real costs, much like any significant commitment in life. These costs can be psychological (the mental effort or emotional strain involved), social (the impact on relationships, community dynamics, or cultural norms), and lifestyle-related (the time, resources, or energy needed to live out those ethics). To understand why societies or individuals adopt certain ethical stances—and why others are out of reach—we need to think about what it “costs” to maintain them and whether those costs are affordable given the available resources.

This perspective shifts our view from simply measuring how ethical a society is to analyzing the trade-offs and constraints that shape its moral landscape. For example, a society might deeply value compassion, but if its members are exhausted from survival struggles or face harsh social penalties for acting altruistically, that compassion may remain dormant or morph into something more pragmatic. Similarly, a society might feel righteous indignation about injustice, but if it lacks the time, wealth, or information to act, that outrage might fizzle out or turn inward. By examining these costs and constraints, we can better predict why ethical behaviors emerge, persist, or fade—and how they might evolve in the future.

Let’s break this down by exploring the key factors that influence the “affordability” of ethical dispositions, drawing on the psychological, social, and lifestyle dimensions we’ve outlined.

Psychological Costs: The Emotional Toll

Ethics often start with our emotions, and these emotions carry a price. Compassion, for instance, requires empathy and care for others, which can be emotionally draining—especially in a world full of suffering. Imagine a nurse in a war zone: their compassion might push them to help others tirelessly, but the constant exposure to pain could lead to burnout or emotional fatigue. Similarly, righteous indignation—an innate sense of outrage at unfairness—can be a powerful driver of ethical action, but if it has no clear target or outlet, it can fester into frustration or cynicism, taxing mental health.

Fear of consequences also plays a role. Living ethically might mean risking punishment, whether from authorities, peers, or even a higher power. This fear can weigh heavily on the mind, making it harder to act on moral impulses. And the desire for belonging—the need to fit in with a group—can create psychological tension if an individual’s ethics clash with societal norms. For instance, someone might feel compelled to support a community’s exclusionary practices to avoid ostracism, even if it conflicts with their sense of fairness.

These emotional costs are relatively stable within individuals but vary across societies based on culture and experience. A society with high compassion might prioritize care-based ethics, but only if its members can bear the emotional burden without collapsing under stress.

Social Costs: The Community Trade-Offs

Ethical dispositions don’t exist in a vacuum—they ripple through social networks, often at a cost. Cultural conditioning, for example, sets the default moral framework of a society, and deviating from those norms can lead to conflict, shaming, or exclusion. If a society is deeply rooted in traditions that discourage change, adopting a new ethical stance—like advocating for equality in a patriarchal culture—can create social tension or even risk exile.

Power structures also shape these costs. In authoritarian settings, challenging the status quo (even for ethical reasons) might invite repression, making justice-driven ethics prohibitively expensive. Conversely, in decentralized societies, ethical debates can flourish, but they might still divide communities, especially if exposure to suffering or injustice sparks disagreement about how to respond. For instance, a community facing poverty might split between those who want to redistribute resources and those who fear losing their own.

Narrative framing by media or leaders adds another layer. When certain ethical issues—say, climate change or racial inequality—are amplified, they can unify or polarize a society. If the framing stokes outrage but doesn’t offer solutions, the social cost of division can be high, making collective action harder to sustain.

These social expenses depend on a society’s willingness to tolerate conflict, its power dynamics, and how its stories shape priorities. A society with rigid norms or centralized control might lean toward conformity, while a flexible, diverse one might afford more ethical experimentation—but at the risk of fragmentation.

Lifestyle Costs: The Practical Burdens

Living ethically often requires real-world resources, and these can be scarce. Free time is a big factor—people with demanding jobs or survival needs might not have the luxury to reflect on abstract moral responsibilities. A farmer in a drought-stricken region, for example, might prioritize feeding their family over pondering global justice, even if they feel compassionate or outraged.

Resource availability is equally critical. Ethical choices—like buying sustainable products, supporting charities, or investing in education—often require money or access to technology. In wealthy societies, people might afford to prioritize environmental ethics, but in poorer ones, survival takes precedence, pushing ethics toward pragmatism.

Environmental pressures, like climate change or natural disasters, can heighten these costs by demanding immediate action over long-term moral goals. Technological capacity can ease or intensify them: advanced tools might make ethical living easier (e.g., renewable energy), but adopting new technologies can also require significant investment or adaptation, adding to the lifestyle burden.

Finally, the flow of information influences how much attention and effort ethics demand. In today’s hyper-connected world, constant news about global issues can overwhelm people, making it harder to focus on ethical action without burning out. In contrast, a society with limited information might miss ethical challenges altogether, keeping costs low but awareness minimal.

Balancing Costs and Resources: The Affordability Threshold

To sustain an ethical disposition, a society needs enough resources to cover these costs. We can think of this as an affordability threshold—the maximum psychological, social, and lifestyle capacity a society has to “pay” for its ethics. This threshold depends on factors like wealth, leisure, technology, and environmental stability, minus the pressures that drain those resources.

For example, a society with abundant resources, free time, and advanced technology might afford compassionate or justice-driven ethics, even if they’re emotionally and socially taxing. But a society under environmental stress, with scarce resources and little leisure, might only afford basic survival ethics, even if its people feel deep compassion or indignation. The gap between the total cost of an ethical stance and this threshold determines whether a society can maintain its ideals—or if it must settle for something more pragmatic.

Real-World Implications

This affordability lens helps explain both historical and contemporary ethical patterns. In medieval Europe, for instance, survival demands, rigid cultural norms, and limited resources made individualistic or equality-based ethics unaffordable for most, leading to a focus on duty, obedience, and divine law. Today, in wealthier, tech-savvy societies, people might afford environmental or social justice ethics, but information overload and social polarization can raise the costs, threatening burnout or inaction.

Looking forward, as climate change intensifies and technology evolves, we might see ethical dispositions shift. Societies with more resources could prioritize sustainability, but those under environmental pressure might revert to survivalist ethics, even if they feel outrage or compassion. Understanding these trade-offs can help predict how ethics will evolve—and where interventions (like education or policy) might lower costs or raise the affordability threshold.

Next Steps

This natural-language exploration sets the stage for a technical model. We could formalize this by quantifying the psychological, social, and lifestyle costs, assigning weights to each factor, and calculating an affordability metric to predict ethical dispositions. But before diving into equations, we’ve established a shared understanding of how ethics are shaped by what societies can “afford” to feel, believe, and do. What aspects of this framework resonate most with you, or where would you like to deepen the analysis before we build the technical model?

Good. Now provide a more technical rendering of that model that should reflect the dynamics of ethical dispositions in society.

Technical Model of Ethical Dispositions: Affordability Dynamics

This model quantifies the ethical disposition (ED) of a society as a function of the total ethical cost (TEC) and the affordability threshold (AT), reflecting the interplay of psychological, social, and lifestyle costs with available resources. The goal is to predict how societal conditions shape ethical stances, capturing both stability and change over time.

1. Definitions and Variables

We’ll use the following variables, normalized to a range of [0, 1] for consistency:

- Ethical Disposition (ED): A scalar value (0 to 1) representing the society’s prevailing ethical stance, where 0 indicates purely pragmatic or survivalist ethics, and 1 reflects highly idealistic or aspirational ethics.

- Total Ethical Cost (TEC): The cumulative cost of sustaining an ethical disposition, broken into psychological expenses (PE), social expenses (SE), and lifestyle expenses (LE).

- Affordability Threshold (AT): The maximum capacity of a society to “pay” for ethics, determined by enabling and constraining factors.

The 13 factors from our framework are:

- Psychological Constants (stable traits, 0 to 1):

- Compassion (C): Empathy and care for others.

- Righteous Indignation (RI): Latent outrage seeking a target.

- Fear of Consequences (F): Anxiety about punishment or retribution.

- Desire for Belonging (B): Need to align with a group.

- Contextual Variables (dynamic influences, 0 to 1):

- Free Time for Reflection (FT): Leisure to ponder ethics.

- Resource Availability (R): Access to material and technological means for ethical choices.

- Cultural Conditioning (CC): Strength of societal norms.

- Exposure to Suffering/Injustice (ES): Awareness of moral triggers.

- Information Flow (IF): Speed and volume of information dissemination.

- Power Structures (PS): Degree of centralized control.

- Environmental Pressures (EP): External survival demands.

- Technological Capacity (TC): Tools enabling ethical options.

- Narrative Framing (NF): Media/leader focus on ethical issues.

2. Model Formulation

Ethical Disposition (ED) emerges when TEC does not exceed AT. If TEC > AT, ED diminishes, reflecting a shift toward more affordable, pragmatic ethics.

a. Total Ethical Cost (TEC)

- Psychological Expenses (PE): The emotional toll of maintaining an ethical stance.

- Squared terms for C and RI reflect exponential emotional drain (e.g., burnout from sustained compassion or indignation).

- Linear terms for F and B indicate less taxing, steady costs.

- Weights

(e.g., 0.4, 0.3, 0.2, 0.1) sum to 1, reflecting relative impact.

- Social Expenses (SE): The communal cost of ethical actions or deviations.

- Linear terms for CC and PS capture steady costs of cultural norms and power dynamics.

- Squared terms for ES and NF reflect escalating costs from division or polarization over suffering and narrative framing.

- Weights

(e.g., 0.2, 0.2, 0.3, 0.3) sum to 1.

- Lifestyle Expenses (LE): The practical cost of living ethically.

- Inverse terms (1 – FT, 1 – R, 1 – TC) reflect higher costs when free time, resources, or technological capacity are scarce.

- Direct terms for EP and IF capture costs from environmental pressures and information overload.

- Weights

(e.g., 0.2, 0.2, 0.2, 0.2, 0.2) sum to 1.

b. Affordability Threshold (AT)

- Sum of enabling factors (R, FT, TC, IF) minus the constraining factor (EP).

(e.g., 0.25) is a scaling constant to match AT’s range (0–1) with TEC.

c. Ethical Disposition (ED)

: Baseline ethical potential from compassion and righteous indignation, normalized to 0–1.

- The

function caps ED at 1 to prevent unrealistic inflation.

- If

, ED decreases, reflecting a shift to more pragmatic ethics as costs exceed capacity.

3. Dynamic Interactions

To capture the evolving nature of ethical dispositions, we can introduce time-dependent changes:

- Temporal Decay: If TEC consistently exceeds AT, ED may decline exponentially over time, modeled as

, where

is a decay rate (e.g., 0.1).

- Feedback Loops: High ES or NF might amplify RI, increasing PE and SE, modeled as

, with

(e.g., 0.05) as a sensitivity parameter.

4. Example Calculation

Consider a hypothetical society:

- Constants: C = 0.7, RI = 0.6, F = 0.4, B = 0.5

- Variables: FT = 0.8, R = 0.6, CC = 0.3, ES = 0.7, IF = 0.9, PS = 0.2, EP = 0.4, TC = 0.7, NF = 0.8

- PE =

- SE =

- LE =

- TEC =

- AT =

- E_base =

- ED =

(or 32.2%)

This society’s high total ethical cost (TEC) (1.313) exceeds its affordability threshold (AT) (0.65), resulting in a low ethical disposition (ED) of 0.322, indicating a shift toward pragmatic ethics despite strong compassion and righteous indignation.

5. Interpretation and Refinement

- High TEC: Reflects the burden of sustained compassion, indignation, social division, and scarce resources.

- Low AT: Limited by environmental pressures despite decent resource availability, free time, and technological capacity.

- Refinement: We could adjust weights, add non-linear terms (e.g.,

), or model temporal dynamics (e.g., adaptation to environmental pressures over time).

This model captures the dynamic interplay of costs and resources, predicting how ethical dispositions evolve based on societal conditions. Would you like to refine specific parameters, test it on a historical case, or explore additional dynamics (e.g., feedback loops or external shocks)?

I would now like you to comment on 1) potential causal recursivities in our model and 2) the malleability of compassion/empathy in contexts of extremely low resources.

Let’s dive into your two thoughtful prompts, offering a detailed, natural-language analysis while maintaining clarity and grounding it in our model of ethical dispositions. I’ll address potential causal circularities in the model and the malleability of compassion/empathy in contexts of extremely low resources, drawing on the 13 factors and the affordability framework we’ve developed.

1. Potential Causal Recursivities in Our Model

Our model of ethical dispositions, framed around the affordability of psychological, social, and lifestyle “expenses,” is designed to predict how societal conditions shape ethical stances. However, complex systems like this often involve causal circularities—feedback loops where factors influence each other in ways that can create dynamic, self-reinforcing (or self-dampening) patterns. Let’s explore some potential circularities and their implications:

- Righteous Indignation (RI) and Exposure to Suffering/Injustice (ES): In the model, RI (latent outrage) can be amplified by ES (awareness of suffering or injustice), which increases psychological and social costs (e.g., PE and SE). But high RI can also heighten attention to and awareness of ES, as outraged individuals seek out or amplify evidence of injustice. For example, a society feeling strong RI might intensify media coverage or activism around ES, which in turn sustains or escalates RI. This creates a feedback loop: RI → ES → RI, potentially driving ethical movements (like civil rights) or escalating social polarization, increasing TEC and straining the affordability threshold (AT).

- Narrative Framing (NF) and Compassion (C)/Righteous Indignation (RI): NF shapes which ethical issues are highlighted, potentially boosting C or RI by focusing attention on suffering or injustice. However, heightened C or RI can influence NF, as compassionate or indignant groups pressure media or leaders to frame issues in ways that align with their values. For instance, a surge in C might lead to narratives emphasizing humanitarian crises, which then further amplify C, creating another circular dynamic: C/RI → NF → C/RI. This can lower AT if it polarizes society, increasing SE, or raise TEC if it demands more emotional investment.

- Resource Availability (R) and Ethical Disposition (ED): R directly affects AT, enabling more idealistic ED by reducing lifestyle expenses (LE). But a high ED (e.g., prioritizing sustainability or justice) can influence how R is allocated—society might redirect resources toward ethical goals, like funding renewable energy or social programs. This creates a loop: R → ED → R, where ethical priorities could either sustain abundance (if successful) or deplete R (if costs outpace gains), impacting TEC and AT over time.

- Environmental Pressures (EP) and Lifestyle Expenses (LE): EP increases LE by demanding survival-focused actions, reducing AT and pushing toward pragmatic ethics. However, a society’s response to EP—driven by its ED (e.g., adopting sustainable practices)—can mitigate or exacerbate EP. For example, a compassionate, resource-rich society might invest in climate solutions, reducing EP, but if resources are scarce, the effort to address EP could heighten LE, creating a feedback loop: EP → LE → ED → EP. This can either stabilize or destabilize ethical dynamics, depending on resource levels.

These circularities suggest our model isn’t just linear—it’s a dynamic system where factors like emotions, narratives, and resources interact in complex ways. To address them, we could refine the model by:

- Introducing time-dependent equations to track feedback loops (e.g.,

, where

is a sensitivity parameter).

- Adding damping or saturation terms to prevent infinite escalation (e.g., capping RI or ES at 1).

- Simulating scenarios to test how circularities affect ED over time, such as under varying R or EP conditions.

Without accounting for these loops, the model might overestimate stability or miss critical tipping points where ethical shifts occur. They highlight the need for a dynamic, iterative approach to predict how ethical dispositions evolve in real-world contexts.

2. The Malleability of Compassion/Empathy in Contexts of Extremely Low Resources

Compassion and empathy—key drivers of ethical dispositions in our model—are often seen as innate human traits, but their expression and intensity can be highly malleable, especially under extreme conditions like extremely low resources. Let’s explore how this plays out and what it means for our model:

- Suppression Under Survival Pressure: When resources (R), free time (FT), and technological capacity (TC) are extremely low, and environmental pressures (EP) are high, survival becomes the immediate priority. In such contexts, compassion and empathy—while potentially present—may be suppressed or redirected. For example, a famine-stricken community might focus on securing food for immediate family members, sidelining broader altruistic impulses. This reflects a shift in lifestyle expenses (LE), where the cost of acting compassionately (e.g., sharing scarce food) outweighs the psychological or social benefits, pushing ethical dispositions toward pragmatism or even self-preservation over care. The affordability threshold (AT) shrinks, making idealistic ethics unaffordable, and ED drops as TEC rises.

- Adaptation and Hardening: Over time, prolonged scarcity can harden compassion or empathy, not because they disappear, but because they adapt to the context. People might develop a form of “selective empathy,” prioritizing those closest to them (e.g., kin or in-group members) over outsiders, as a survival strategy. This aligns with cultural conditioning (CC) and desire for belonging (B), where norms evolve to favor in-group loyalty, reducing the psychological cost (PE) of excluding others. For instance, historical accounts of siege or drought often show communities becoming more insular, with compassion reserved for the “deserving” few, reflecting a malleable ethical stance shaped by resource scarcity.

- Potential for Resilience: Despite low resources, compassion and empathy can persist or even surge in rare cases, driven by exposure to suffering/injustice (ES) or narrative framing (NF). If a leader or story emphasizes shared suffering (e.g., “We’re all in this together”), it might mobilize collective compassion, lowering social expenses (SE) through unity. However, this requires some minimal R or FT to act on those feelings, and if EP is overwhelming, even strong C might be overwhelmed by survival needs, increasing LE and reducing ED.

- Long-Term Malleability: Over generations, extremely low resources can reshape cultural conditioning (CC), embedding pragmatic or survivalist ethics into societal norms, potentially diminishing baseline compassion. But exposure to external aid, technological breakthroughs, or shifts in information flow (IF) could rekindle empathy, as people reconnect with broader human concerns. This suggests C isn’t fixed—it’s highly flexible, shaped by both immediate pressures and long-term societal adaptations.

In our model, the malleability of compassion/empathy under low resources has significant implications:

- It underscores the need to adjust PE dynamically, perhaps with a function like

, where low R reduces C’s impact, and

(e.g., 0.5) reflects sensitivity to scarcity.

- It highlights the interplay with CC, ES, and NF, where cultural narratives can either suppress or amplify C, affecting SE and AT.

- It suggests a potential threshold effect: below a certain R or FT level, C might effectively drop to near zero, driving ED toward survivalist ethics unless external factors intervene.

This malleability challenges the assumption that compassion is a constant, urging us to model it as context-dependent, especially under extreme environmental pressures (EP) and resource scarcity (R). It also reinforces the model’s afford ability framework, showing how ethical dispositions adapt to survive in harsh conditions, potentially leading to long-term shifts in societal values.

Would you like me to refine these insights further—perhaps by simulating specific scenarios, adjusting the model mathematically, or exploring historical examples of compassion under resource scarcity? Let me know how you’d like to proceed!

Now create the Mermaid Chart code that will accurately reflect our basic model of the dynamics of ethical dispositions.

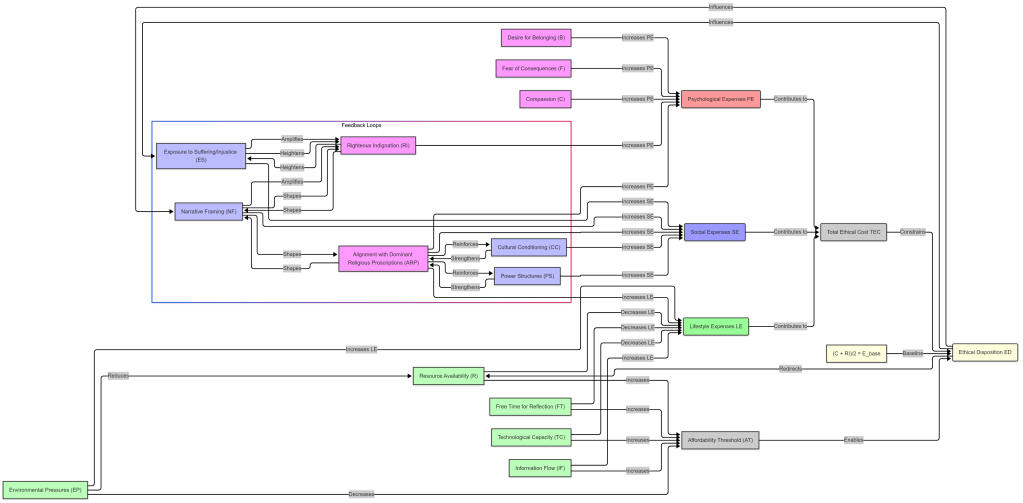

Explanation of the Mermaid Chart

- Structure:

- The chart is a directed graph (flowchart) showing how the 13 factors contribute to psychological expenses (PE), social expenses (SE), and lifestyle expenses (LE), which sum to total ethical cost (TEC).

- Affordability threshold (AT) is influenced by enabling factors (R, FT, TC, IF) and constrained by EP, determining ethical disposition (ED) alongside a baseline E_base (derived from C and RI).

- Arrows indicate causal relationships (e.g., C increases PE), with direction showing influence.

- Key Components:

- Psychological Factors (C, RI, F, B): Colored in pink (#f9f), feeding into PE (red, #f99).

- Social Factors (CC, PS, ES, NF): Colored in light blue (#bbf), feeding into SE (blue, #99f).

- Lifestyle Factors (FT, R, EP, TC, IF): Colored in light green (#bfb), feeding into LE (green, #9f9).

- TEC, AT, and ED are in gray (#ccc) and yellow (#ffd) to distinguish aggregated and outcome variables.

- Dynamics and Feedback:

- The subgraph “Feedback Loops” highlights circularities, such as ES and NF amplifying RI, and RI influencing ES and NF.

- ED feeds back to influence ES, NF, and R, reflecting how ethical stances redirect resources or shape narratives.

- EP reduces R, and ED can redirect R, capturing resource allocation dynamics.

- Notes:

- The chart simplifies the mathematical model but retains core relationships, like TEC constraining ED when it exceeds AT.

- Colors and strokes enhance readability, but you can adjust styling in Mermaid for your needs.

You can paste this code into a Mermaid-compatible tool (e.g., Mermaid Live Editor, or a WordPress plugin like Mermaid Chart) to generate the visual. If you’d like to refine it—adding more details, adjusting layout, or focusing on specific loops—let me know, and I can tweak the code accordingly!

It appears we are missing a key variable: Alignment with dominant religious proscriptions. Add this to our model and Mermaid chart.

You’re absolutely right—adding Alignment with Dominant Religious Proscriptions (ARP) as a key variable enriches our model of ethical dispositions, as religious beliefs often profoundly shape ethical norms, especially through cultural, social, and psychological pathways. I’ll integrate ARP into our affordability framework, updating both the natural-language description of the model and the Mermaid Chart code to reflect this new factor. Here’s how we’ll approach it:

Updated Model: Incorporating Alignment with Dominant Religious Proscriptions (ARP)

Alignment with Dominant Religious Proscriptions (ARP) represents the degree to which a society’s ethical dispositions align with or are constrained by prevailing religious doctrines, rules, or moral codes. This variable, normalized to a range of 0 to 1 (where 0 = no alignment, and 1 = complete adherence), can influence ethical dynamics in several ways:

- Psychological Impact: ARP can amplify or suppress compassion (C), righteous indignation (RI), fear of consequences (F), or desire for belonging (B), depending on whether religious teachings promote certain emotions or impose guilt/shame for deviation. For example, a religion emphasizing divine love might boost C, while one focused on sin and punishment might heighten F.

- Social Impact: ARP often reinforces cultural conditioning (CC) and power structures (PS), as religious authorities can enforce norms or exert control. High ARP might increase social expenses (SE) by raising the cost of deviating from religious ethics (e.g., ostracism or excommunication), but it could also reduce SE by fostering unity under shared beliefs.

- Lifestyle Impact: ARP can affect lifestyle expenses (LE) by dictating practices (e.g., fasting, tithing, or ritual observance) that require time (FT) or resources (R). In contexts of low resources, adhering to ARP might become unaffordable, reducing ED or shifting ethics toward pragmatism.

Given these dynamics, ARP will primarily influence psychological expenses (PE), social expenses (SE), and potentially lifestyle expenses (LE), while also interacting with other factors like narrative framing (NF) and cultural conditioning (CC).

Updated Technical Model

I’ll modify the existing model to include ARP, adjusting the equations and relationships. Here’s the updated formulation, with LaTeX equations enclosed in tags for WordPress compatibility:

- New Variable: Alignment with Dominant Religious Proscriptions (ARP) (0 to 1).

- Updated Total Ethical Cost (TEC):

- Psychological Expenses (PE) (updated to include ARP):

- The squared term for ARP reflects exponential psychological costs (e.g., guilt, fear, or cognitive dissonance) when adhering to or resisting religious proscriptions.

- Weights

(e.g., 0.3, 0.25, 0.15, 0.1, 0.2) sum to 1, reflecting relative impact.

- Social Expenses (SE) (updated to include ARP):

- A linear term for ARP captures steady social costs (e.g., conformity pressures or penalties for deviation).

- Weights

(e.g., 0.15, 0.15, 0.25, 0.25, 0.2) sum to 1.

- Lifestyle Expenses (LE) (updated to include ARP, if relevant):

- A linear term for ARP reflects lifestyle costs (e.g., time or resource demands of religious practices).

- Weights

(e.g., 0.15, 0.15, 0.15, 0.15, 0.15, 0.25) sum to 1.

- Affordability Threshold (AT) and Ethical Disposition (ED) remain unchanged:

(with

= 0.25, for example).

, where

.

- Dynamic Interactions: ARP can create new feedback loops, such as:

- ARP reinforcing CC and PS, which in turn strengthen ARP:

, where

(e.g., 0.05) is a sensitivity parameter.

- ARP influencing NF, which shapes C and RI, and vice versa.

- ARP reinforcing CC and PS, which in turn strengthen ARP:

This update adds complexity but enhances realism, especially for societies where religion drives ethical norms.

Explanation of Updates to the Mermaid Chart

- New Node: Added Alignment with Dominant Religious Proscriptions (ARP) (labeled as “W”) in pink (#f9f), grouped with psychological factors, as it influences PE, SE, and LE.

- Connections:

- ARP connects to PE, SE, and LE, reflecting its psychological, social, and lifestyle costs.

- In the “Feedback Loops” subgraph, ARP reinforces CC and PS, which strengthen ARP, and interacts with NF, capturing religious influence on narratives and vice versa.

- Styling: ARP uses the same pink fill (#f9f) as other psychological factors for consistency, ensuring visual coherence.

This updated model and chart now account for the critical role of religion in shaping ethical dispositions, adding depth to our affordability framework.

Now, let’s apply our model to ethical dispositions found at various times in history. Let’s begin with the practice of killing or leaving female newborns to die. Provide 1) the model calculus, 2) the prose explanation, and 3) the Mermaid Chart.

Let’s apply our updated model of ethical dispositions—incorporating the 13 factors plus Alignment with Dominant Religious Proscriptions (ARP)—to analyze the historical practice of killing or abandoning female newborns, a phenomenon observed in various ancient societies (e.g., ancient Greece, Rome, and parts of Asia). This practice, often tied to economic, social, and cultural pressures, offers a compelling case to test our model’s dynamics. I’ll provide:

- The Model Calculus: A mathematical application of the model, using the formulas and variables from our framework, with specific values for the historical context.

- The Prose Explanation: A natural-language interpretation of the model’s results, explaining why this practice emerged and persisted in terms of affordability and ethical dynamics.

- The Mermaid Chart: An updated Mermaid Chart reflecting the specific dynamics for this historical case, highlighting key factors and interactions.

I’ll focus on ancient Greece (e.g., 7th–4th centuries BCE) as a representative example, where female infanticide was documented due to economic constraints, patriarchal norms, and resource scarcity. Let’s dive in.

1. The Model Calculus

We’ll use the technical model from our previous updates, applying estimated values for the 14 factors (including ARP) to calculate the ethical disposition (ED) for the practice of killing or abandoning female newborns. The model equations are:

- Total Ethical Cost (TEC):

- Psychological Expenses (PE):

- Weights:

,

,

,

,

(summing to 1).

- Weights:

- Social Expenses (SE):

- Weights:

,

,

,

,

(summing to 1).

- Weights:

- Lifestyle Expenses (LE):

- Weights:

,

,

,

,

,

(summing to 1).

- Weights:

- Affordability Threshold (AT):

.

- Ethical Disposition (ED):

.

Estimated Values for Ancient Greece (Female Infanticide Context)

Based on historical records (e.g., economic scarcity, patriarchal norms, and religious influences like Greek polytheism prioritizing male heirs):

- C (Compassion) = 0.3: Low, as societal norms devalued female infants, but some compassion existed (e.g., maternal grief).

- RI (Righteous Indignation) = 0.2: Very low, as the practice was culturally accepted, minimizing outrage.

- F (Fear of Consequences) = 0.6: Moderate, due to economic survival pressures and social expectations.

- B (Desire for Belonging) = 0.8: High, as conforming to patriarchal norms was critical for social acceptance.

- FT (Free Time for Reflection) = 0.2: Low, due to survival demands in agrarian societies.

- R (Resource Availability) = 0.3: Low, due to scarce resources and economic pressures favoring male labor.

- CC (Cultural Conditioning) = 0.9: Very high, as patriarchal norms and gender roles were rigid.

- ES (Exposure to Suffering/Injustice) = 0.4: Moderate, as female infanticide was normalized but some families felt moral conflict.

- IF (Information Flow) = 0.2: Low, limited to oral traditions and local norms.

- PS (Power Structures) = 0.7: High, with male-dominated governance enforcing patriarchal ethics.

- EP (Environmental Pressures) = 0.7: High, due to resource scarcity and agricultural challenges.

- TC (Technological Capacity) = 0.3: Low, with limited tools for resource management.

- NF (Narrative Framing) = 0.5: Moderate, with religious and cultural narratives supporting male-centric values.

- ARP (Alignment with Dominant Religious Proscriptions) = 0.8: High, as Greek religion (e.g., Zeus, Athena) often prioritized male lineage and societal roles, reinforcing the practice.

Calculations

- Psychological Expenses (PE):

=

= 0.027 + 0.01 + 0.09 + 0.08 + 0.128 = 0.335 - Social Expenses (SE):

=

= 0.135 + 0.105 + 0.04 + 0.0625 + 0.16 = 0.5025 - Lifestyle Expenses (LE):

=

= 0.12 + 0.105 + 0.105 + 0.105 + 0.03 + 0.2 = 0.665 - Total Ethical Cost (TEC):

- Affordability Threshold (AT):

- Baseline Ethical Potential (E_base):

- Ethical Disposition (ED):

(or 1.25%)

This extremely low ED (1.25%) indicates that the practice of killing or abandoning female newborns was pragmatically affordable and ethically dominant in this context, driven by high costs and a low affordability threshold.

2. Prose Explanation

In ancient Greece, the practice of killing or abandoning female newborns was a grim but widespread ethical disposition, deeply rooted in the societal conditions of the time. Our model reveals why this practice persisted by framing it as an “affordable” ethical choice under extreme constraints, where the psychological, social, and lifestyle costs of alternative behaviors (e.g., raising female infants equally) far exceeded the society’s affordability threshold.

Psychologically, compassion and righteous indignation were low (C = 0.3, RI = 0.2), as cultural norms normalized female infanticide, minimizing emotional conflict. However, fear of economic ruin and social ostracism (F = 0.6, B = 0.8) drove individuals to conform, adding to the psychological expense. The alignment with dominant religious proscriptions (ARP = 0.8), such as Greek polytheistic beliefs prioritizing male heirs (e.g., lineage for Zeus or Apollo), further reinforced this, creating guilt or pressure to adhere, increasing psychological costs.

Socially, rigid cultural conditioning (CC = 0.9) and male-dominated power structures (PS = 0.7) made deviating from this practice costly, raising social expenses through potential exclusion or shame. Exposure to the suffering of female infants (ES = 0.4) existed but was muted by normalization, while narrative framing (NF = 0.5) supported male-centric values, adding to social division costs. ARP amplified these social pressures, as religious norms aligned with patriarchal ethics, making alternative stances (e.g., valuing female life equally) socially unaffordable.

Lifestyle-wise, the society faced severe resource scarcity (R = 0.3), limited free time for reflection (FT = 0.2), and high environmental pressures (EP = 0.7) from agrarian challenges, making it impractical to raise additional mouths, especially females seen as less economically productive. Low technological capacity (TC = 0.3) and slow information flow (IF = 0.2) further constrained options, while ARP added lifestyle costs through religious obligations (e.g., rituals favoring male lineage), pushing total lifestyle expenses high.

The affordability threshold (AT = 0.075) was extremely low due to scarce resources and high environmental pressures, while the total ethical cost (TEC = 1.5025) of maintaining an alternative ethical stance (e.g., preserving female infants) was prohibitively high. As a result, the ethical disposition (ED = 0.0125) leaned heavily toward pragmatism, making female infanticide the dominant, affordable choice. This low ED reflects a survivalist ethic where economic and social survival trumped compassion or justice, despite some latent emotional potential (E_base = 0.25).

- Specific Values: I’ve added the estimated values for each factor (e.g., C = 0.3) to the nodes, providing context for ancient Greece’s female infanticide practice.

- Emphasis on Key Drivers: The chart highlights CC, PS, ARP, R, and EP as dominant influences, with weaker feedback loops for C, RI, and ED, reflecting their suppression in this context.

- Feedback Loops: The subgraph emphasizes the strong reinforcement between ARP, CC, PS, and NF, driving the high TEC and low AT.

- Styling: Colors and strokes remain consistent with the previous chart, ensuring visual continuity.

Over time, shifts in R, EP, or NF (e.g., philosophical critiques like those of Plato or Aristotle) might have raised AT or lowered TEC, but in this period, the practice persisted due to its affordability under harsh conditions.

Notes on the Mermaid Chart

This application demonstrates how our model explains historical ethical practices through affordability dynamics, offering a quantitative and visual framework for analysis.

Let’s apply the model to a scenario in which much public media is emphasizing the sentience of octopi and there is reasonably-priced lab-produced meat indistinguishable from the taste of octopi.

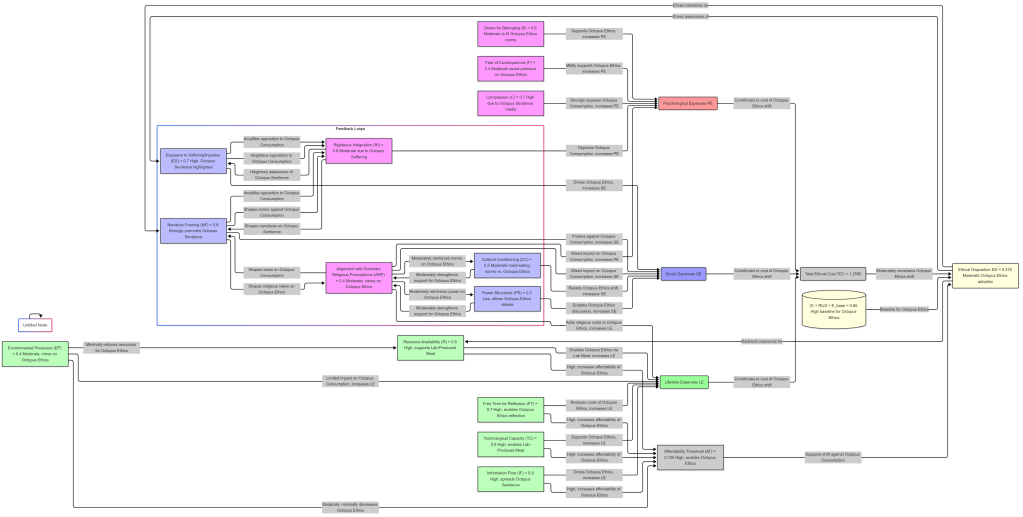

Let’s apply our updated model of ethical dispositions—incorporating the 14 factors (including Alignment with Dominant Religious Proscriptions (ARP))—to a contemporary social scenario where media emphasizes the sentience of octopi, and there’s reasonably priced, lab-produced meat indistinguishable from octopus in taste. This scenario reflects a potential ethical shift toward vegetarianism or reduced octopus consumption, driven by media narratives, technological advances, and consumer choices. I’ll provide:

- The Model Calculus: A mathematical application of the model, using estimated values for the factors to calculate the ethical disposition (ED).

- The Prose Explanation: A natural-language interpretation of the model’s results, explaining why this ethical shift might occur or face challenges.

- The Mermaid Chart: An updated Mermaid Chart reflecting the specific dynamics for this scenario, highlighting key factors and interactions.

I’ll assume this scenario occurs in a modern, developed society (e.g., a Western country in 2025) with access to technology, media, and resources, but with varying cultural and religious influences.

1. The Model Calculus

We’ll use the technical model from our previous updates, applying estimated values for the 14 factors to calculate the ethical disposition (ED) for adopting an ethical stance against consuming octopus due to its sentience, facilitated by lab-produced meat. The model equations are:

- Total Ethical Cost (TEC):

- Psychological Expenses (PE):

- Weights:

,

,

,

,

(summing to 1).

- Weights:

- Social Expenses (SE):

- Weights:

,

,

,

,

(summing to 1).

- Weights:

- Lifestyle Expenses (LE):

- Weights:

,

,

,

,

,

(summing to 1).

- Weights:

- Affordability Threshold (AT):

.

- Ethical Disposition (ED):

.

Estimated Values for the Octopus Sentience Scenario (Modern Developed Society, 2025)

Based on the scenario where media emphasizes octopus sentience and lab-produced meat is available:

- C (Compassion) = 0.7: High, as media narratives highlight octopus sentience, evoking empathy.

- RI (Righteous Indignation) = 0.6: Moderate to high, as awareness of octopus sentience sparks outrage against consumption.

- F (Fear of Consequences) = 0.4: Moderate, due to mild social pressure or guilt but low legal risk.

- B (Desire for Belonging) = 0.6: Moderate, as social norms shift but not universally, creating some conformity pressure.

- FT (Free Time for Reflection) = 0.7: High, as modern societies have more leisure to ponder ethics.

- R (Resource Availability) = 0.8: High, with access to lab-produced meat and economic stability.

- CC (Cultural Conditioning) = 0.5: Moderate, as traditional meat-eating norms coexist with emerging ethical shifts.

- ES (Exposure to Suffering/Injustice) = 0.7: High, due to media focus on octopus sentience and suffering.

- IF (Information Flow) = 0.9: Very high, with rapid media dissemination via social platforms.

- PS (Power Structures) = 0.3: Low, as decentralized modern societies allow ethical debate without strong top-down control.

- EP (Environmental Pressures) = 0.4: Moderate, with some climate concerns but not overwhelming survival pressures.

- TC (Technological Capacity) = 0.9: Very high, with lab-produced meat technology available.

- NF (Narrative Framing) = 0.8: High, as media strongly frames octopi as sentient, ethical beings.

- ARP (Alignment with Dominant Religious Proscriptions) = 0.4: Moderate, as religious views vary (some support animal ethics, others prioritize human needs).

Calculations

- Psychological Expenses (PE):

=

= 0.147 + 0.09 + 0.06 + 0.06 + 0.032 = 0.389 - Social Expenses (SE):

=

= 0.075 + 0.045 + 0.1225 + 0.16 + 0.08 = 0.4825 - Lifestyle Expenses (LE):

=

= 0.045 + 0.03 + 0.06 + 0.015 + 0.135 + 0.1 = 0.385 - Total Ethical Cost (TEC):

- Affordability Threshold (AT):

- Baseline Ethical Potential (E_base):

- Ethical Disposition (ED):

(or 37.5%)

This ED of 37.5% suggests a moderate ethical disposition toward reducing octopus consumption, driven by high compassion and media influence, but tempered by social and lifestyle costs.

2. Prose Explanation

In this modern scenario, where media emphasizes the sentience of octopi and reasonably priced, lab-produced meat indistinguishable from octopus is available, we’re witnessing a potential ethical shift toward reducing or eliminating octopus consumption. Our model shows why this shift is plausible but not fully realized, framed as an “affordable” ethical choice under current societal conditions, with some constraints.

Psychologically, compassion and righteous indignation are high (C = 0.7, RI = 0.6), as media narratives about octopus sentience evoke empathy and outrage against their consumption. Fear of social judgment (F = 0.4) is moderate, reflecting mild guilt or peer pressure, while the desire for belonging (B = 0.6) pushes some to adopt vegetarianism to fit emerging ethical norms. Alignment with dominant religious proscriptions (ARP = 0.4) has a moderate impact, as religious views vary—some support animal ethics, while others prioritize human dietary traditions, adding psychological costs but not overwhelmingly.

Socially, cultural conditioning (CC = 0.5) is moderate, as traditional meat-eating norms coexist with growing ethical awareness, creating some social tension but not rigid opposition. Power structures (PS = 0.3) are low, allowing decentralized ethical debates to flourish, but exposure to octopus suffering (ES = 0.7) and narrative framing (NF = 0.8) drive social momentum toward change, raising social expenses through discussions and potential polarization. ARP adds moderate social costs, as religious communities may resist or support the shift, depending on doctrine.

Lifestyle-wise, the society benefits from high resource availability (R = 0.8), ample free time for reflection (FT = 0.7), and advanced technological capacity (TC = 0.9), making lab-produced meat an affordable alternative to octopus consumption. Environmental pressures (EP = 0.4) are moderate, not overriding ethical considerations, and high information flow (IF = 0.9) amplifies media narratives, but these factors increase lifestyle costs through attention demands and adaptation to new dietary habits. ARP adds lifestyle costs through potential religious dietary restrictions, but these are manageable given the affordability of lab meat.

The affordability threshold (AT = 0.725) is relatively high due to abundant resources and technology, while the total ethical cost (TEC = 1.2565) of adopting an anti-octopus consumption stance is moderate, driven by psychological and social efforts to shift norms. The resulting ethical disposition (ED = 0.375) indicates a moderate shift toward ethical behavior—many might reduce or eliminate octopus consumption, especially with lab meat as an alternative, but traditional habits, social inertia, and religious views prevent a full transformation. Over time, increased NF, ES, or TC could raise ED, but current costs and cultural resistance temper the change.

3. Mermaid Chart

I’ll update the Mermaid Chart to reflect the specific dynamics for this scenario, emphasizing C, RI, NF, ES, TC, and R as key drivers for the ethical shift against octopus consumption, while noting constraints from CC, B, and ARP. Here’s the updated Mermaid Chart code with tags referencing octopus sentience and lab-produced meat:

Write an essay that assesses the potential accuracy and utility of models created to assess the ethical disposition of a society given various factors. Comment on the possibility of other similar projects that could produce valuable models or analyses.

Assessing the Accuracy and Utility of Modeling Ethical Dispositions in Society

In an era defined by rapid technological, cultural, and environmental change, understanding the ethical fabric of societies has become both a pressing need and a complex challenge. Developing a model to assess the ethical disposition of a society, as we’ve explored through our affordability framework, offers a promising tool for predicting, analyzing, and influencing moral behaviors. However, the accuracy and utility of such a model hinge on its design, assumptions, and applications, as well as its ability to navigate the inherent complexities of human ethics. This essay evaluates the strengths and limitations of our model, grounded in the 14 factors—including compassion, righteous indignation, and alignment with religious proscriptions—and considers the potential for similar projects to generate valuable models or analyses.

The Accuracy of Modeling Ethical Dispositions

The accuracy of a model like ours depends on its ability to faithfully represent the multifaceted nature of ethical dispositions while accounting for their dynamic, context-dependent evolution. Our model, which frames ethical dispositions as outcomes of psychological, social, and lifestyle “expenses” balanced against an affordability threshold, captures key drivers such as compassion, resource availability, and cultural conditioning. By quantifying these factors and their interactions—using variables like compassion (C), righteous indignation (RI), and narrative framing (NF)—the model provides a structured way to predict how societies might respond to ethical dilemmas, as demonstrated in our analyses of historical female infanticide and contemporary octopus sentience debates.

However, accuracy faces several challenges. First, ethical dispositions are deeply subjective and culturally specific, making it difficult to assign universal, precise values to factors like compassion or fear of consequences. Our normalization of variables (0 to 1) simplifies this complexity, but it risks oversimplifying nuanced emotional and cultural differences. For instance, in the female infanticide case, we estimated low compassion (C = 0.3) in ancient Greece, but individual variation or unrecorded dissent might skew these figures. Second, the model assumes linear or exponential relationships (e.g., squared terms for compassion to reflect burnout), but human ethics often exhibit non-linear, threshold-based behaviors—emotions might suddenly surge or dissipate under specific conditions, like extreme resource scarcity, which our model might miss without fine-tuning.

Third, causal circularities—such as righteous indignation amplifying exposure to suffering, which in turn heightens indignation—introduce feedback loops that can destabilize predictions if not modeled dynamically. While we’ve addressed these with time-dependent equations (e.g., ), accurately parameterizing these loops requires robust historical or empirical data, which may be incomplete or biased. Finally, the model’s reliance on static weights (e.g., w_C = 0.3) assumes a fixed hierarchy of influence, but these weights likely vary across cultures, eras, and contexts, undermining precision without continuous calibration.

Despite these limitations, the model’s accuracy is bolstered by its flexibility. By integrating diverse factors—psychological (e.g., compassion), social (e.g., power structures), and lifestyle (e.g., resource availability)—it captures the interplay of individual emotions and societal structures. Its quantitative nature also allows for testing and refinement, such as adjusting weights based on historical data or simulations, as seen in our case studies. However, achieving high accuracy requires ongoing validation against real-world ethical shifts, rigorous data collection, and sensitivity analysis to account for uncertainty.

The Utility of Modeling Ethical Dispositions

The utility of our model lies in its potential to inform policy, education, and societal interventions by predicting ethical trends and identifying leverage points. For instance, in the octopus sentience scenario, a moderate ethical disposition (ED = 0.375) suggests that media narratives and lab-produced meat could drive a shift away from octopus consumption, but cultural resistance and lifestyle costs limit full adoption. Policymakers could use this insight to target public campaigns (enhancing narrative framing (NF)) or subsidize lab meat (boosting resource availability (R)) to lower total ethical costs (TEC) and raise the affordability threshold (AT).

Similarly, the model’s application to female infanticide revealed how resource scarcity and patriarchal norms made compassionate alternatives unaffordable, offering historical lessons for addressing gender inequality today. By simulating different factor values—e.g., increasing resource availability or challenging cultural conditioning—stakeholders can explore “what-if” scenarios to foster ethical progress, such as promoting gender equity or animal welfare.

The model’s utility extends beyond prediction to education and reflection. It provides a framework for scholars, ethicists, and citizens to debate societal values, understand trade-offs, and recognize the interplay of emotions, culture, and resources. For example, it highlights how low free time or high environmental pressures can suppress compassion, prompting discussions on work-life balance or sustainability policies. However, its utility is limited by data availability—without accurate, granular inputs, predictions may be speculative—and by its complexity, which could alienate non-expert audiences unless simplified for communication.

Possibilities for Similar Projects

The approach of modeling ethical dispositions opens the door to a range of related projects that could produce valuable models or analyses, addressing other societal dynamics or ethical domains. Here are a few promising avenues:

- Environmental Ethics Models: A model similar to ours could assess societal dispositions toward climate action, incorporating factors like environmental pressures (EP), technological capacity (TC), and narrative framing (NF) around climate change. By quantifying compassion for nature and righteous indignation at pollution, such a model could predict adoption of green technologies or resistance to fossil fuels, guiding environmental policy and activism.

- Technological Ethics Models: With the rise of AI and biotechnology, a model could evaluate ethical dispositions toward these innovations, using factors like information flow (IF), power structures (PS), and exposure to suffering/injustice (ES) related to privacy or inequality. This could help anticipate public acceptance of AI governance or genetic editing, informing regulatory frameworks.

- Global Inequality Models: A project could model ethical dispositions toward global poverty or migration, integrating resource availability (R), cultural conditioning (CC), and alignment with religious proscriptions (ARP). By assessing compassion and indignation across nations, such a model could guide humanitarian aid strategies or immigration policies, identifying cultural barriers or opportunities for solidarity.

- Intergenerational Ethics Models: Focusing on obligations to future generations, a model could explore factors like technological capacity (TC), environmental pressures (EP), and narrative framing (NF) around sustainability or debt. This could predict societal commitment to long-term planning (e.g., climate mitigation) versus short-term pragmatism, informing education or governance initiatives.

These projects would share our model’s strengths—quantifying complex dynamics, revealing trade-offs, and guiding interventions—but face similar challenges: data limitations, cultural variability, and the risk of oversimplification. To maximize value, they could draw on interdisciplinary methods, combining sociology, psychology, and economics, and leverage big data (e.g., social media sentiment for NF, economic indicators for R) to refine parameters. Collaborative efforts, involving ethicists, technologists, and policymakers, could ensure relevance and applicability, while open-source platforms could foster global input and validation.

Conclusion

Our model of ethical dispositions offers a powerful, if imperfect, tool for understanding and shaping societal ethics. Its accuracy is constrained by the subjectivity of human values, data gaps, and dynamic complexities, but its utility in predicting ethical shifts and informing action is substantial, as demonstrated in historical and contemporary cases. By refining the model with empirical data, dynamic simulations, and broader stakeholder engagement, we can enhance its precision and impact. Moreover, the potential for similar projects—modeling environmental, technological, or global ethics—underscores a fertile field for future research, promising deeper insights into humanity’s moral landscape. Ultimately, such models are not just analytical tools but invitations to reflect on what societies can afford to value—and how we might expand that capacity for a more ethical future.

◉ Note that this exercise reflects a moral non-realist perspective and is largely a Machiavellian attempt to merely describe and predict phenomena often categorized as “moral” or “ethical.”

ChatGPT 03-mini-high‘s Assessment of Grok’s Performance:

Below is a markdown table providing a rigorous assessment of Grok’s performance along several key dimensions:

| Comments | |

|---|---|---|

| Organization and Structure | A | The content is well-organized, with clearly delineated sections, numbered steps, and a logical progression from conceptual framing to a technical model. |

| Clarity and Readability | A | Despite the inherent complexity of the topic, the explanation remains clear, and the use of numbered lists and headings aids in understanding. |

| Comprehensiveness and Depth | A | Grok covers a broad range of factors—psychological, social, and lifestyle—and provides an in-depth discussion of each aspect, including potential limitations and next steps. |

| Mathematical Rigor | B | The model is presented in a clear, additive framework with interaction terms, but it remains preliminary and conceptual, with room for more advanced analysis and empirical validation. |

| Innovation and Creativity | A | The integration of ethical dynamics with an affordability framework is novel and demonstrates creative thinking in tackling a complex, multi-dimensional topic. |

| Practical Applicability | B | While the model offers a promising conceptual framework, its practical application would benefit from further empirical tuning and validation to handle real-world complexities. |

Table of Contents: (Click any link below to navigate to that section.)

- Can you produce a preliminary mathematical model of ethical dynamics based on these (previously brainstormed) factors?

- Let’s attempt to frame our model in terms of the “affordability” of ethical dispositions based on the psychological, social, and lifestyle “expenses”. Produce a coherent framework in these terms.

- Good. Now provide a more technical rendering of that model that should reflect the dynamics of ethical dispositions in society.

- I would now like you to comment on 1) potential causal circularities in our model and 2) the malleability of compassion/empathy in contexts of extremely low resources.

- Now create the Mermaid Chart code that will accurately reflect our basic model of the dynamics of ethical dispositions.

- It appears we are missing a key variable: Alignment with dominant religious proscriptions. Add this to our model and Mermaid chart.

- Now, let’s apply our model to ethical dispositions found at various times in history. Let’s begin with the practice of killing or leaving female newborns to die. Provide 1) the model calculus, 2) the prose explanation, and 3) the Mermaid Chart.

- Let’s apply the model to a scenario in which much media is emphasizing the sentience of octopi and there is reasonably-priced lab-produced meat indistinquishable from the taste of octopi.

- Write an essay that assesses the accuracy and utility of producing a model to assess the ethical disposition of a society given various factors. Comment on the possibility of other simila projects that could produce valuable models or analyses.

Leave a comment