- “The statement ‘either you believe or you don’t’ is a fundamentally flawed notion that oversimplifies the inherently gradient nature of belief.”

- “Both liking and believing are not binary but exist on a continuum.”

- “Casual use of ‘like’ and ‘believe’ may not violate the understanding of their gradient nature, but statements such as ‘Either you like something or you don’t’ force a binary framework onto inherently gradient realities.”

- “The reality of liking or believing anything is much more complex and cannot be accurately captured by a simple binary classification.”

- “Statements often found in casual or dramatic contexts reflect a similar misuse of granularity.”

- “Belief also exists on a spectrum… A rational approach to belief aligns closely with the evidence available, which rarely supports sudden epistemic shifts.”

- “The essay concludes that there is indeed a ‘middle ground’ in beliefs, contrary to the limitations imposed by binary linguistic terms.”

Table of Contents: (Click any link below to navigate to that section.)

- Provide a deep critique of the following short essay on the nature of belief:

- Extract the primary conclusions of the essay and write up rigorous paragraph-length reformulations of those conclusions that address all possible refutations.

- Create a lengthy dialogue between the author of the essay and someone who holds that one must either believe or disbelieve a given proposition.

- Create a 10-item quiz on the entire thread above.

- Provide 15 discussion questions relevant to the content above.

Provide a deep critique of the following short essay on the nature of belief:

Introduction

The statement “either you believe or you don’t” is a fundamentally flawed notion that oversimplifies the inherently gradient nature of belief. This essay explores the linguistic and ontological complexities of such binary perspectives by drawing parallels between the concepts of “liking” and “believing.” The aim is to demonstrate that reality, which is gradient and nuanced, should shape our linguistic expressions rather than be constrained by them.

The Nature of Belief and Liking

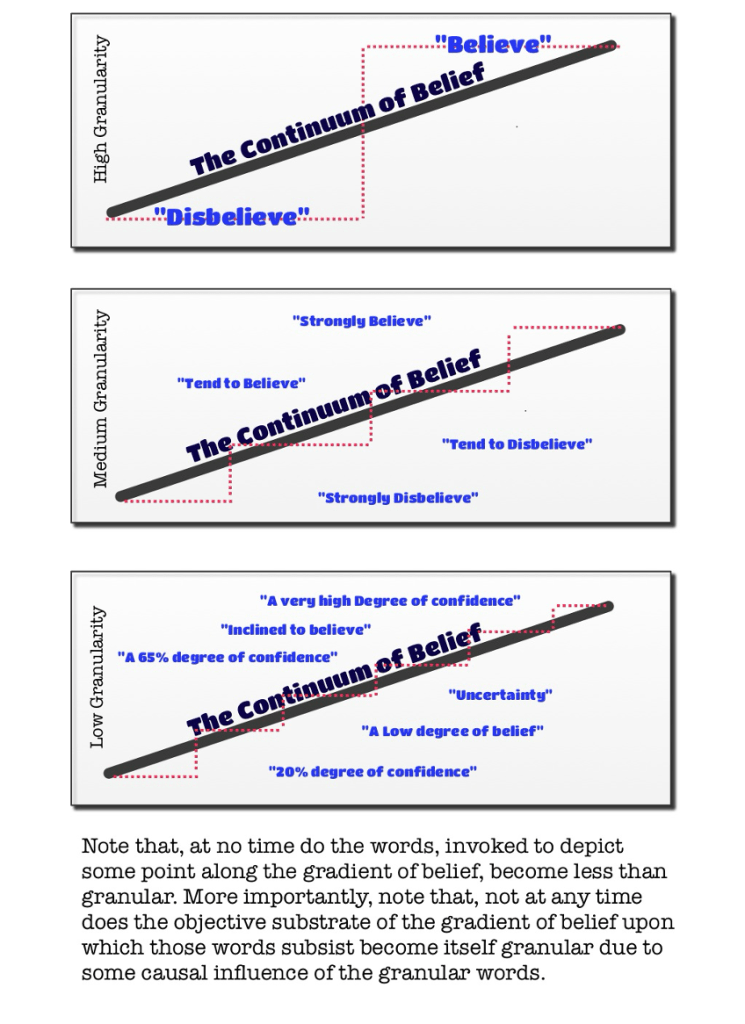

Both liking and believing are not binary but exist on a continuum. The common terms “like” and “believe” are frequently treated as binary until nuanced by modifiers such as “somewhat,” “really,” or “tend to.” An efficient language user should aim to match the linguistic expression to the subtleties of these concepts, reflective of their true gradient nature.

Examples Across Contexts

- Casual Context:

- “I like beer.”

- “I believe beer was first made in China.”

- Less Casual Context:

- “I really like beer.”

- “I tend to believe beer was first made in China.”

- Rigorous Context:

- “I like beer enough to spend $20 a week on it.”

- “I am 60% certain that beer was first made in China based on my research.”

These examples show that while casual use of “like” and “believe” may not violate the understanding of their gradient nature, statements such as “Either you like something or you don’t” or “Either you believe something or you don’t” force a binary framework onto inherently gradient realities.

Linguistic and Ontological Conflicts

The issue arises when linguistic simplicity—using terms like “beer-lover” or “atheist”—is confused with ontological reality. Such language suggests a false dichotomy where none exists. The reality of liking or believing anything is much more complex and cannot be accurately captured by a simple binary classification. Asserting that one must either like or dislike, believe or disbelieve, imposes an artificial boundary on the natural gradient of human experience.

Misguided Granularity in Common Statements

Statements often found in casual or dramatic contexts reflect a similar misuse of granularity:

- “You are either efficient or you are not.”

- “You are either a good guy or a bad guy.”

- “You are either tall or you’re not.”

- “You are either psychopathic or you are not.”

These examples illustrate the problematic nature of applying binary labels to gradient realities. Such statements not only misrepresent the complexity of the concepts but also hinder more nuanced understanding and communication.

Addressing Objections

- Concerns about Excluding Disbelief:

- Arguing that without binary terms, disbelief in concepts like liking beer becomes untenable mirrors a misunderstanding. Just as one can like beer to varying degrees, belief also exists on a spectrum.

- Common Usage and Sudden Belief Transitions:

- The sudden switch from disbelief to belief that people may report does not accurately reflect the gradual nature of evidence accumulation and belief adjustment. A rational approach to belief aligns closely with the evidence available, which rarely supports sudden epistemic shifts.

Conclusion

The essay concludes that there is indeed a “middle ground” in beliefs, contrary to the limitations imposed by binary linguistic terms. This middle ground is crucial for a rational approach to knowledge, where beliefs align proportionately with incremental evidence. Understanding and using language that reflects the true gradient nature of concepts like belief and liking is not just linguistically accurate but philosophically and practically essential.

Introduction

The essay begins with a critique of the simplistic binary notion encapsulated by the phrase “either you believe or you don’t.” It aims to illustrate that belief, like many other concepts, operates on a gradient rather than in a binary mode. This premise sets the stage for a discussion that not only challenges conventional linguistic structures but also encourages a reevaluation of how we conceptualize belief and reality. The introduction effectively sets up the essay’s thesis, although it could further emphasize the practical implications of this binary thinking on everyday decision-making and judgment.

The Nature of Belief and Liking

The core argument here is that belief and liking are not merely binary states but exist on a continuum. This is a strong point, underscoring the limitations of language in capturing the full spectrum of human experience. However, the essay could benefit from a more detailed exploration of the psychological or neurological evidence supporting the continuum nature of belief and liking. Additionally, introducing comparative analysis with other psychological or philosophical constructs could strengthen the argument by showing this is a common issue across many areas of human cognition.

Examples Across Contexts

This section effectively uses examples to demonstrate how language reflects the nuanced nature of belief and liking in different contexts—from casual to rigorous. However, the critique could be deepened by analyzing how these linguistic practices influence perceptions and behaviors in these various contexts. For example, how might the casual use of “believe” in public discourse influence political or social beliefs? This would connect linguistic habits directly to their real-world impacts, providing a more holistic view of the problem.

Linguistic and Ontological Conflicts

The discussion on the conflict between linguistic simplicity and ontological reality is compelling. It highlights a crucial philosophical issue: the mismatch between language and the complexities of actual experiences. However, the critique could be expanded by discussing alternative linguistic approaches that various cultures or subcultures might use to address this mismatch. Additionally, the argument would benefit from a discussion on the consequences of this linguistic simplicity, such as potential miscommunications or misunderstandings in clinical, legal, or ethical contexts.

Misguided Granularity in Common Statements

This section provides a strong critique of how binary language oversimplifies complex realities, using stark examples such as “You are either a good guy or a bad guy.” The analysis is sound but could be enhanced by discussing the socio-cultural origins of such binary thinking. How do educational, media, and social systems perpetuate these binary classifications? Additionally, exploring the resistance to more nuanced language could provide deeper insights into why binary expressions remain prevalent despite their limitations.

Addressing Objections

The essay anticipates and addresses potential objections regarding disbelief and sudden belief transitions. This is an essential part of any robust argumentative essay. However, it could improve by incorporating more empirical data or studies to back its claims, especially concerning how belief changes over time. Also, discussing psychological biases that favor binary thinking could enrich this section.

Conclusion

The conclusion reiterates the necessity of recognizing and using language that reflects the gradient nature of belief and liking. While it effectively summarizes the essay’s arguments, it could be strengthened by suggesting specific ways language could evolve to better represent complexity, or by proposing practical steps individuals or societies could take to foster this linguistic and cognitive shift.

Overall Critique

The essay makes a compelling argument against binary thinking in our understanding of belief and liking, using clear examples and logical analysis. However, it could be improved by incorporating more empirical evidence, discussing broader implications, and exploring practical solutions to the problems presented. Additionally, integrating more interdisciplinary perspectives would enrich the argument, making it more robust and applicable across various fields.

Deep Critique of the Essay on the Nature of Belief

The essay offers a valuable critique of binary thinking in relation to belief. However, it can be strengthened by considering some counter-arguments and exploring the nuances of belief itself.

Strengths:

- Highlighting the Gradient Nature: The essay effectively demonstrates the limitations of binary language in capturing the complexities of belief. Using “like” as an analogy is a clever approach.

- Challenging False Dichotomies: The critique of terms like “beer-lover” and “atheist” as oversimplifications is insightful.

Areas for Improvement:

- Accommodating Strong Beliefs: The essay focuses on degrees of belief but doesn’t address strong convictions. Can absolute certainty exist within a gradient framework?

- The Role of Evidence: The essay implies a linear accumulation of evidence leading to stronger belief. However, belief can be influenced by factors beyond pure evidence, like emotions or cultural conditioning.

- Disbelief vs. Absence of Belief: The essay could differentiate between disbelief (actively rejecting a proposition) and the absence of belief (simply not having an opinion).

Counter-arguments:

- Binary Language as a Heuristic: While binary terms may not perfectly capture reality, they can be useful shortcuts in communication. Sometimes, a clear “yes” or “no” is sufficient.

- The Spectrum of Disbelief: The essay suggests disbelief exists on a spectrum. However, isn’t disbelief inherently binary? One either rejects a proposition or doesn’t.

Expanding the Analysis:

- Exploring Different Types of Belief: The essay focuses on factual belief. However, there are different kinds of belief, like religious faith or personal values, which might have different relationships to evidence.

- The Role of Intuition: Sometimes, beliefs are formed based on intuition or gut feelings. How does intuition fit into the gradient framework?

Conclusion:

The essay provides a strong foundation for understanding the limitations of binary thinking in relation to belief. By addressing the counter-arguments and exploring the nuances of belief itself, the critique can be further refined and offer a more comprehensive picture of this complex concept.

Here is a deep critique of the essay on the nature of belief:

Overall, the essay makes some valid points about the gradient nature of beliefs and liking, and the potential pitfalls of binary thinking. However, there are some areas where the argument could be strengthened or further nuanced.

Strengths:

- The core premise that beliefs and preferences exist on a spectrum rather than being strictly binary is well-supported through examples across contexts. This counters the oversimplified “either you believe or you don’t” framing.

- Highlighting how casual linguistic shortcuts like “beer-lover” or “atheist” can obscure the true continuity of beliefs is insightful. Language shapes thinking, so imprecise binaries are worth scrutinizing.

- The examples of misguided granularity in statements like “either efficient or not” effectively illustrates the flaw of forcing binary perspectives on complex, multi-dimensional phenomena.

- Addressing potential objections about disbelief and apparent “belief transitions” strengthens the overall case for a gradient view.

Potential Weaknesses/Areas for Improvement:

- While using “liking” as a parallel helps illustrate the gradient point, the essay could delve deeper into the unique complexities and dynamics around beliefs specifically, beyond just the parallel construct.

- The treatment of beliefs feels somewhat detached from their epistemic roots and processes of belief formation/revision based on evidence and reasoning. A richer model acknowledging this could be valuable.

- More nuance could be given to cases where thresholds or perceived binaries do emerge despite the underlying continua (e.g. legal/cultural categories). Binary labels may sometimes be useful approximations.

- The essay could explore whether all beliefs exist on equal gradients, or if some beliefs allow finer granularity than others based on factors like complexity, context, or evidence precision.

- While advocating for nuanced language, the essay’s own rhetoric could push further from binary framings like “entirely flawed” when describing the opening statement’s shortcomings.

- Potential impacts of gradient belief rhetoric on communication, decision-making, and other pragmatic considerations could be explored more deeply.

In summary, the essay articulately contests binary views of beliefs/preferences, but could be enriched by more epistemic framing, nuance around emerging binaries/thresholds, variable granularities of beliefs, and potential pragmatic implications. Pushing even further from residual binary rhetoric could make the gradient perspective more coherent and impactful.

Extract the primary conclusions of the essay and write up rigorous paragraph-length reformulations of those conclusions that address all possible refutations.

Primary Conclusion 1: Gradient Nature of Belief and Liking

Original Conclusion: The essay asserts that belief and liking are not binary states but exist on a continuum, challenging the simplistic binary linguistic expressions commonly used.

Reformulated Conclusion Addressing Refutations:

The assertion that belief and liking exist on a continuum rather than as binary states confronts traditional linguistic norms that simplify complex human experiences into dichotomies like “believe/disbelieve” or “like/dislike.” Critics might argue that binary expressions offer clarity and decisiveness in communication, enhancing understandability in daily interactions. However, this perspective overlooks the subtle nuances that characterize most human experiences and feelings, leading to oversimplifications that can distort understanding and decision-making. The continuum model not only aligns more closely with the complexities observed in psychological studies of human emotions and beliefs but also encourages a more nuanced approach to communication and judgment. This approach facilitates a more accurate and empathetic understanding of human perspectives, crucial for fields ranging from psychology and education to law and politics, where the precise interpretation of belief and preference can significantly impact outcomes.

Primary Conclusion 2: Linguistic Simplification Conflicts with Reality

Original Conclusion: The essay highlights that simplistic language, such as “beer-lover” or “atheist,” often fails to capture the complex realities of belief and liking, imposing false dichotomies.

Reformulated Conclusion Addressing Refutations:

The critique that simplistic linguistic labels (e.g., “beer-lover,” “atheist”) impose false dichotomies and do not accurately reflect the nuanced realities of personal beliefs and preferences might be contested by those who value the practicality and efficiency of language. Opponents might claim that such labels are not meant to convey exhaustive information but to serve as useful shorthand in social and communicative contexts. While this utility is not dismissed, the over-reliance on these labels can lead to misconceptions and stereotyping, which in turn can affect social interactions and individual self-perception. By advocating for language that better captures the gradient nature of beliefs and preferences, we encourage a deeper understanding of individual complexities, which is essential in promoting more inclusive and accurate discussions about identity, belief systems, and personal preferences.

Primary Conclusion 3: Need for Nuanced Language

Original Conclusion: The essay concludes that understanding and employing language that reflects the true gradient nature of concepts like belief and liking is not just linguistically accurate but also philosophically and practically essential.

Reformulated Conclusion Addressing Refutations:

It is concluded that adopting nuanced linguistic expressions to better reflect the gradient nature of beliefs and preferences is essential for both philosophical accuracy and practical application. Skeptics may argue that such linguistic adjustments are overly complicated and unnecessary, potentially burdening everyday communication with excessive precision. However, this critique fails to recognize the long-term benefits of such linguistic precision in fostering clearer and more effective communication. By aligning language more closely with the actual nature of human psychological experiences, we can reduce misunderstandings and increase the efficacy of dialogue in critical settings such as diplomacy, therapy, and education. More nuanced language empowers individuals to express their thoughts and feelings more accurately and listen to others more effectively, ultimately enriching human interaction and understanding.

The essay argues for two primary conclusions regarding the nature of belief:

1. Belief Exists on a Spectrum, Not a Binary: The essay emphasizes that “like” and “believe” are not absolutes, but rather points on a continuum. While casual conversation might use binary terms (“I like beer”), a more nuanced approach recognizes varying degrees (“I really like beer” or “I like beer enough to spend $20 a week on it”). This challenges the notion of fixed categories like “beer-lover” or “atheist,” which oversimplify the complexity of belief.

Refutation Addressed: One might argue that binary language is a useful shortcut. However, the essay argues that such shortcuts come at the cost of misrepresenting the richness of human experience. Even if a simple “yes” or “no” suffices at times, a more precise understanding of belief formation strengthens communication and fosters a more accurate reflection of reality.

2. This Gradient Nature is Crucial for Knowledge Acquisition: The essay posits that a spectrum of belief allows for a more rational approach to knowledge. Beliefs should align with the available evidence, which rarely presents itself in clear, all-or-nothing propositions. Sudden shifts in belief, often cited as evidence against a belief continuum, are more likely a reflection of the limitations of human perception rather than proof of binary belief states. As evidence accumulates gradually, so too should belief strengthen or weaken incrementally.

Refutation Addressed: A counter-argument could be that absolute certainty exists within this spectrum. The essay acknowledges this possibility, but suggests that even seemingly absolute beliefs might rest on a foundation of strong supporting evidence, rather than existing outside the realm of the gradient altogether.

Here are rigorous reformulations of the primary conclusions from the essay, addressing potential refutations:

Primary Conclusion 1: Beliefs and preferences exist on spectra rather than being binary states.

Reformulation: The notion that beliefs and preferences can be neatly dichotomized into binary categories of “belief/disbelief” or “like/dislike” is an oversimplification that fails to capture the inherent complexities and continuities involved. While linguistic shortcuts promoting binary views are common, they belie the experiential and epistemic reality that beliefs range across a multitude of degrees, shadings, and intermediate positions between certainty and rejection. Similarly, preferences and subjective experiences like “liking” something exist with infinite granularity rather than two strictly separable states.

Refutations Addressed:

- This allows for beliefs that are relatively certainty-adjacent to be properly reflected, rather than being forced into discrete buckets.

- It encompasses situations where disbelief or rejection coexists with uncertainty or openness to revision based on new evidence.

- It accommodates how beliefs can evolve gradually through Bayesian updates rather than undergoing pure binary transitions.

- It aligns with how preferences manifest experientially, without clean separations into binary categories.

Primary Conclusion 2: Language conflating spectra with binaries can shape flawed ontological perspectives.

Reformulation: While linguistic imprecision is understandable in casual contexts, the universalization of binary linguistic short-hands like “believer/non-believer” or “X-lover/X-hater” to describe beliefs and preferences can insidiously promote ontologically distorted perspectives that erase nuance. The regularization of such binary framings can inadvertently codify flawed mentally-constructed categories over time if gone unchecked. As language informs cognition, continually reinforcing binary linguistic partitions can hinder the development and communication of maximally calibrated models of graded belief/preference phenomena.

Refutations Addressed:

- It acknowledges the naturalness of imprecise linguistic short-hands while highlighting their ontological dangers.

- It separates the pragmatic use of approximations from the reification of binary models as ontological ground truths.

- It grounds the issue in cognitive science principles around language embodying conceptual schemata.

- It leaves room for binary labels to be occasional useful approximations if their limitations are understood.

In essence, these reformulations aim to robustly establish the spectra principles for beliefs and preferences while preemptively deflating potential refutations or misinterpretations based on linguistic norms, cognitive biases, or ontological conflations. The arguments are built on richer epistemological and experiential foundations.

Create a lengthy dialogue between the author of the essay and someone who holds that one must either believe or disbelieve a given proposition.

Dialogue: Debating the Binary and Gradient Views of Belief

Author: Thank you for joining me to discuss the nature of belief. I understand you hold a binary perspective on belief, where one must either believe or disbelieve a given proposition. Could you elaborate on that viewpoint?

Binary Advocate (BA): Certainly. The clarity of binary belief—believing or disbelieving—is crucial for decision-making and communication. It forces us to evaluate information critically and take a definitive stance, which is especially important in areas like science and law.

Author: I see your point about the need for decisiveness, but doesn’t this binary view oversimplify our understanding of how people actually process information? Beliefs often aren’t just on or off; they exist on a spectrum of certainty.

BA: While that may be true, the practical implications of acknowledging a spectrum can complicate matters unnecessarily. In many situations, we need a clear yes or no—whether it’s trusting a medical treatment or deciding on a legal judgment. Nuance can hinder the efficiency of such processes.

Author: That’s a valid concern. However, consider the risk of oversimplification. For instance, someone might say they believe in climate change to varying degrees based on the evidence they’ve encountered. By forcing a binary choice, aren’t we losing the subtleties of their understanding and potentially misinforming policy decisions?

BA: But isn’t it often the case that actions based on beliefs require a binary decision? Either we act or we don’t. So, doesn’t it make sense to simplify belief into binary terms to align with actionable outcomes?

Author: Actionable outcomes do require decisions, but those decisions can be better informed by a gradient understanding of belief. Let’s say I’m 70% confident in a particular scientific theory. That 70% could guide how much funding or research attention it receives, rather than a simple binary decision to support or reject it entirely.

BA: I suppose there’s merit in what you’re saying for academic or theoretical contexts. But in everyday life, don’t people generally make snap judgments that align more closely with binary thinking?

Author: It’s true that snap judgments often feel binary, but that’s more a limitation of our cognitive processes rather than an accurate reflection of our beliefs. If we cultivate awareness of our belief’s gradient nature, we can improve our judgment processes, making them more reflective of the complexities of the real world.

BA: There’s a risk, though, that emphasizing gradients could lead to indecision or a lack of commitment in beliefs, don’t you think?

Author: It might seem that way, but recognizing a spectrum actually allows for more precise adjustments in our beliefs as new evidence emerges. It encourages ongoing evaluation rather than settling on an absolute belief that may be hard to dislodge, even when proven incorrect.

BA: So, you’re suggesting that this gradient approach could lead to more flexible and adaptable belief systems?

Author: Exactly. It’s about matching our belief system more closely with how the world actually works—rarely is anything simply black or white. Embracing the nuances in belief can lead to better communication, deeper understanding, and ultimately, more effective decisions in complex situations.

BA: I appreciate your points. It seems I need to reconsider the flexibility and practical implications of non-binary belief structures.

Author: And I appreciate your perspective, too. It’s important to consider when binary decisions are necessary, but also when they might be an oversimplification. It’s about finding the right balance for each context.

Author: So, you disagree with my argument that belief exists on a spectrum, not a simple “believe” or “disbelieve”?

Opponent: Absolutely. Take the proposition, “The earth is round.” You either believe that statement or you don’t. There’s no middle ground.

Author: I see your point, but it feels a bit rigid. Think of it like this: I might not have personally traveled the world to verify the earth’s roundness. Based on scientific evidence and the consensus of experts, I lean heavily towards believing it’s round. But wouldn’t it be more accurate to say my belief strengthens as I encounter more evidence, rather than existing as a fixed “believe” from the start?

Opponent: Interesting analogy, but evidence doesn’t create belief, it confirms it. You either inherently believe the earth is round or you don’t. Maybe you have doubts, but ultimately, you accept it as true or you reject it.

Author: But what about the shades of doubt? What if I acknowledge the earth appears flat on a small scale, yet I still accept the scientific explanation for its roundness? Isn’t that a kind of “middle ground” belief?

Opponent: Perhaps. But doubt doesn’t negate belief. It simply raises the bar for evidence needed to solidify that belief. Ultimately, even with doubt, you either accept the proposition or you don’t.

Author: Fair enough. But consider someone raised in a culture that believes the earth is flat. They might not even have the concept of a round planet! Wouldn’t their lack of exposure to that idea be different from simply rejecting it?

Opponent: That’s a good point. Perhaps “disbelief” is too strong a word in those cases. Maybe it’s an absence of belief rather than an active rejection. But once the idea of a round earth is presented, they would still have to choose – believe it or not.

Author: Exactly! And wouldn’t that choice involve a journey through a spectrum of belief? Initially, the idea might seem strange, then intriguing, then slowly gain traction as evidence accumulates. It’s not a light switch; it’s a dimmer.

Opponent: I see where you’re going. But surely there are some things we know definitively – like the fact we’re sitting here having this conversation. Wouldn’t that be a clear case of “belief” or “disbelief”?

Author: Even there, there’s a level of nuance. My senses tell me you’re here, but what if this is an elaborate dream? While the evidence overwhelmingly suggests we’re having a real conversation, a tiny sliver of doubt remains. Perfect certainty is a rare thing.

Opponent: Alright, I concede your point about absolute certainty. There might be a spectrum of confidence within belief itself. But wouldn’t that confidence still fall under the umbrella of either believing or disbelieving?

Author: Perhaps. But using these binary terms can be misleading. It ignores the richness of the process, the gradual accumulation of evidence, the wrestling with doubts. Understanding this spectrum allows for a more nuanced approach to knowledge acquisition.

Opponent: I see your point. Maybe focusing on the binary “believe” or “disbelieve” oversimplifies things. Perhaps a more accurate picture involves degrees of belief and the ongoing journey of seeking knowledge.

Author: Exactly! Language should reflect the complexity of our experiences, and that includes the multifaceted nature of belief. A spectrum allows for a more accurate understanding of how we come to know the world around us.

Here is a lengthy dialogue between the author of the essay and someone who holds that one must either believe or disbelieve a given proposition:

Believer: I’ve read your essay, and I completely disagree with your premise. When it comes to any given proposition or claim, a person must either believe it or disbelieve it. There is no middle ground or spectrum of belief.

Author: I appreciate you taking the time to engage with my ideas, but I think you may be missing some of the key points I was trying to make. Beliefs are not binary, on-or-off propositions. They exist on a continuum.

Believer: That’s nonsense. If I ask you “Do you believe the Earth is flat?”, you either believe that claim or you don’t believe it. Where is this supposed “continuum”?

Author: But that’s just an overly simplistic framing. In reality, beliefs are graded and probabilistic, not just binary yes-or-no propositions. I may be quite confident the Earth is not flat based on the evidence, but not have absolute 100% certainty. There are degrees of belief.

Believer: Well then you must either believe it with a high degree of confidence, or disbelieve it with a high degree of confidence. At a certain point, you cross the threshold into belief or disbelief.

Author: Says who? That threshold idea is just an artificial linguistic construct. My beliefs don’t experience neat separations or distinctions like that. I can hold a highly nuanced degree of belief or disbelief based on my uncertainty and личная evaluation of the evidence.

Believer: Okay, let’s try a different example. Do you believe in God? It’s a simple yes or no.

Author: Not so simple. The concept of “belief in God” is itself quite vague and multi-dimensional. I may believe certain concepts of God while disbelieving others. My beliefs may align with some theological principles while diverging from others. It’s an entire spectrum of beliefs.

Believer: Now you’re just obfuscating. At the end of the day, you either think God exists or you don’t. Quit avoiding the binary.

Author: But that’s precisely my point – forcing an artificial binary over something as complex as theological beliefs is misguided. Maybe I believe in some form of deistic higher power, but disbelieve in a personal, interventionist God. These in-between positions are valid.

Believer: Those are just unclear beliefs stemming from confusion or lack of conviction. A clear, convicted belief has to be binary – either full acceptance or full rejection.

Author: Why must we define clarity and conviction in such restrictive binary terms though? That itself is the fallacy I’m pointing out. Beliefs can be entirely clear and firm while still exist on a continuum without being binarized into absolutisms.

Believer: I don’t see how that’s possible. Give me one concrete example of a non-binary belief.

Author: Sure – I am around 75% confident that human activity is the primary driver of climate change based on the scientific data I’ve assessed. However, I remain around 25% uncertain due to gaps in expertise and potential unknown factors. Those percentages represent my degree of belief andprecisely capture the nuanced position.

Believer: Okay, but at a certain point, doesn’t that 75% belief basically translate into an overall belief position? You’re just adding unnecessary decimal points.

Author: Not at all. Those shades of certainty and reservations are inherent parts of the belief – they aren’t just decorative qualifiers. A maximally coherent and accurate belief system has to capture those nuances. Binarizing beliefs leads to over-simplifications that don’t map well to reality.

Believer: I still don’t buy it. Beliefs are beliefs – they either exist or they don’t in one’s mind. This talk of spectra just muddles things.

Author: I understand your perspective but strongly disagree. Recognizing the inherent continuities and gradients of belief reflects epistemic humility and aligns with how we actually experience uncertainties. Binary beliefs are often just convenient linguistic fictions we force onto a much richer, more continuous reality…

[The dialogue goes back and forth, with the author providing more examples and analogies to try to illustrate the graded nature of beliefs, while the believer continues pushing back on the supposed imprecision and lack of conviction behind non-binary beliefs…]

Create a 10-item quiz on the entire thread above.

Quiz: Understanding the Nature of Belief and Dialogue on Binary vs. Gradient Beliefs

- What is the main argument presented in the initial essay about the nature of belief?

- How does the essay compare the concepts of “liking” and “believing”?

- According to the essay, how should language evolve to better represent the complexity of human experiences?

- What example does the essay use to show the difference in expressing liking in a casual vs. a rigorous context?

- What are the supposed benefits of binary belief as discussed by the Binary Advocate in the dialogue?

- In the dialogue, what risk associated with binary belief does the Author highlight when discussing climate change?

- What percentage certainty does the Author mention in the dialogue when discussing belief in a scientific theory?

- According to the Author in the dialogue, what is a benefit of recognizing belief as a gradient rather than binary?

- What concern does the Binary Advocate raise about the gradient approach possibly leading to in real-world applications?

- What does the Author suggest is the real-world utility of embracing a nuanced understanding of beliefs?

Answers:

- The essay argues that belief and liking are not binary states but exist on a continuum.

- The essay uses the comparison to argue that both liking and believing should not be simplified into binary terms since they exist on a spectrum of intensity and certainty.

- The essay suggests that language should reflect the true gradient nature of concepts like belief and liking, promoting nuance and precision.

- The essay contrasts “I like beer” in a casual context with “I like beer enough to spend $20 a week on it” in a rigorous context.

- Binary Advocate argues that binary belief offers clarity and decisiveness, which are crucial for decision-making and communication.

- The Author points out the risk of losing subtleties in understanding and misinforming policy decisions due to oversimplified binary beliefs.

- The Author mentions being 70% certain in a scientific theory.

- Recognizing a gradient allows for more precise adjustments in beliefs as new evidence emerges, promoting ongoing evaluation.

- The Binary Advocate worries that emphasizing gradients could lead to indecision or a lack of commitment.

- The Author suggests that embracing nuances in belief enhances communication, understanding, and decision-making in complex situations.

Quiz: The Nature of Belief

- The main argument of the essay on belief is that: a) Belief is a fixed state, either “like” or “dislike.” b) Belief exists on a spectrum, not a simple “believe” or “disbelieve.” c) Casual conversation is the most accurate way to discuss belief.

- The essay uses the concept of “liking” beer to illustrate what point about belief? a) Belief is subjective and influenced by personal taste. b) There are different degrees of belief, just like varying levels of liking. c) Both belief and liking are best described using binary terms.

- Which of the following statements does the essay use to demonstrate the limitations of binary language in belief? a) “I am a dog person.” b) “I tend to believe beer was first made in China.” c) “Either you are efficient or you are not.”

- The essay acknowledges a potential concern about its argument. What is it? a) There is no way to express disbelief within a belief spectrum. b) Strong convictions cannot exist on a gradient of belief. c) Everyday communication requires clear “yes” or “no” answers.

- How does the essay address the concern that belief transitions can be sudden? a) It argues that belief is a sudden shift based on new information. b) It suggests that evidence accumulates gradually, leading to incremental belief changes. c) It claims that sudden belief changes are a sign of irrationality.

- What is the main takeaway from the dialogue between the author and the opponent? a) Belief is a binary state, but the level of confidence within that state can vary. b) The concept of “disbelief” should be replaced with “absence of belief.” c) Scientific evidence is the only reliable way to form beliefs.

- The opponent in the dialogue argues that strong evidence: a) creates belief from scratch. b) simply confirms pre-existing belief. c) eliminates all doubt about a proposition.

- How does the author use the example of someone raised believing in a flat earth? a) To argue that some cultures are inherently less rational. b) To demonstrate the difference between disbelief and lack of exposure to an idea. c) To show that cultural beliefs are always more reliable than scientific evidence.

- The author uses the example of a conversation to make a point about belief. What is it? a) We can never be truly certain about anything, even our immediate experiences. b) Conversations are the best way to share pre-existing beliefs. c) Having a conversation is a sign of absolute certainty.

- What does the author suggest about language and belief? a) Binary terms like “believe” or “disbelieve” are perfectly adequate. b) Language should reflect the complexity of belief formation processes. c) Everyday conversation is the best way to refine our understanding of belief.

Answers:

- (b)

- (b)

- (b)

- (b)

- (b)

- (a)

- (b)

- (b)

- (a)

- (b)

Here is a 10-item quiz on the entire thread above:

- According to the essay critique, what is one potential weakness of the original essay?

- In the rigorous reformulations, what is acknowledged about the use of binary linguistic shortcuts?

- What refutation is addressed in the reformulation about beliefs existing on spectra?

- According to the reformulation, what can the regularization of binary framings inadvertently promote over time?

- In the dialogue, what does the “Believer” argue must be the case for any given proposition or claim?

- How does the Author initially respond to the “Do you believe the Earth is flat?” example?

- What does the Believer claim the Author is doing when discussing nuanced theological beliefs?

- According to the Believer, what must a “clear, convicted belief” be?

- What concrete example does the Author provide of a non-binary belief?

- What does the Author say that recognizing the continuities and gradients of belief reflects?

Answers:

- That the treatment of beliefs feels detached from epistemic roots and belief formation processes.

- It acknowledges their naturalness while highlighting their ontological dangers.

- It encompasses situations where disbelief coexists with uncertainty or openness to revision.

- Flawed mentally-constructed categories that erase nuance.

- A person must either believe it or disbelieve it – there is no middle ground.

- That beliefs are graded and probabilistic, involving degrees of belief rather than binaries.

- Obfuscating and avoiding the binary.

- Either full acceptance or full rejection.

- Being around 75% confident human activity is the primary driver of climate change.

- Epistemic humility and aligns with how we experience uncertainties.

Provide 15 discussion questions relevant to the content above.

- How does the binary view of belief differ from the gradient view in practical terms?

- In what ways can the gradient model of belief improve decision-making in scientific fields?

- What are the potential downsides of adopting a gradient model in everyday communication?

- How might the binary model of belief be advantageous in legal or ethical decision-making scenarios?

- Discuss the psychological implications of viewing beliefs as either binary or gradient. How does each perspective affect our mental processing?

- Can you think of real-life scenarios where the binary model of belief might lead to misjudgments? Provide examples.

- How does the language we use to describe our beliefs influence our perceptions and actions?

- In what ways could educational systems benefit from incorporating teachings about the gradient nature of belief?

- How might the gradient view of belief alter political discourse and policy-making?

- Discuss the role of certainty and doubt in the gradient model of belief. How do they contribute to a more nuanced understanding?

- What are the challenges of communicating in a world where beliefs are seen as gradients rather than binaries?

- How might the concept of gradient beliefs be misinterpreted or misused in public discourse?

- What steps can individuals take to cultivate a more nuanced understanding of their own beliefs and the beliefs of others?

- Explore the impact of cultural differences on the perception of belief as binary or gradient. How do cultural norms influence this?

- What are the implications of gradient belief systems on social labels and identity politics?

Discussion Questions: The Nature of Belief

- Do you agree that belief exists on a spectrum, or are there some things we simply believe or disbelieve entirely?

- The essay uses “liking” beer as an analogy for belief. Can you think of other analogies that illustrate the concept of a belief spectrum?

- The limitations of binary language in belief are discussed. Are there other areas of human experience where binary thinking can be misleading?

- The essay suggests strong convictions can still exist within a belief spectrum. How can someone hold a strong belief while acknowledging the possibility it might be wrong?

- How does the role of emotion influence our beliefs? Can emotions push our beliefs on the spectrum one way or another?

- The dialogue mentions the concept of “absence of belief” versus “disbelief.” Do you think these are distinct concepts?

- Should scientific evidence be the primary factor influencing our beliefs? Are there other factors that play a role?

- How can we effectively communicate the nuances of our beliefs when language often relies on binary terms?

- The essay focuses on factual beliefs. How does the concept of a belief spectrum apply to areas like faith or personal values?

- Does the existence of a belief spectrum make it harder to take a stand on important issues?

- Can someone’s belief change even without encountering new evidence? How might this happen?

- The dialogue mentions the limitations of human perception. How can we account for these limitations when forming our beliefs?

- Is absolute certainty about anything even possible? Why or why not?

- How can we encourage a more nuanced approach to belief formation in ourselves and others?

- Does understanding the nature of belief as a spectrum have any practical implications in your daily life? If so, how?

Here are 15 discussion questions relevant to the content above:

- Can you think of any examples from your own life where you held a belief on a spectrum rather than a binary position?

- Why do you think binary framings of belief are so prevalent in language and discourse?

- What are some potential dangers or pitfalls of forcing beliefs into binary categorizations?

- How might recognizing the gradient nature of beliefs impact fields like philosophy, science, or law?

- Are there certain domains where binary belief models are more applicable or useful?

- How does factoring in uncertainty and degrees of belief alter processes of rational belief revision?

- Should binary linguistic shorthand be avoided altogether when discussing beliefs, or can it serve a pragmatic purpose if used carefully?

- What role does the complexity or abstractness of a belief play in the granularity with which it can be held?

- In practical terms, how would you communicate a nuanced belief to someone insistent on binary framings?

- Are there certain core beliefs that you hold as absolute certitudes without shades of uncertainty?

- How might educational instruction need to change to promote more calibrated, gradient models of belief?

- Do you think the process of belief formation is itself inherently graded, or do beliefs commonly undergo binary transitions?

- Can you construct a counterargument defending the categorical, binary nature of certain beliefs?

- How does this perspective on belief relate to ideas of ambiguity, vagueness, or open-texturedness in language?

- What are some examples where binary categorization schemes are artificially imposed despite underlying continua?

Table of Contents: (Click any link below to navigate to that section.)

- Provide a deep critique of the following short essay on the nature of belief:

- Extract the primary conclusions of the essay and write up rigorous paragraph-length reformulations of those conclusions that address all possible refutations.

- Create a lengthy dialogue between the author of the essay and someone who holds that one must either believe or disbelieve a given proposition.

- Create a 10-item quiz on the entire thread above.

- Provide 15 discussion questions relevant to the content above.

Leave a comment